On June 4, ICE’s Acting Director Todd Lyons released a video decrying critics of the embattled agency for “stirring up outrage” with their “ridiculous rhetoric and inflammatory comments.” Lyons’ basic argument is that ICE’s officers are doing good work (“protecting” the public), and the critics are having bad effects (“these are real people with real families you’re hurting”). So, the critiques are illegitimate.

The crux:

Law enforcement’s common sense. Politicians need to stop putting my people in danger. I’m not asking them to stop. I’m demanding that they stop.

I find this argument—the very form of it—painfully unserious.1 So I was disappointed to see, just two days later, much the same coming from the stalwart socialist ‘stacker Freddie de Boer.

de Boer was calling out Josh Barro, who had been urging Democrats to push back against labor unions on certain issues in blue cities, where (Barro argues) union policies make it harder to cheaply provide high-quality hotel rooms, subway trips, and affordable housing:

When I look at policies in New York that stand in the way of abundance, very often if you look under the hood, you eventually find a labor union at the end that’s the driver.

Now, maybe de Boer thinks that Barro is really advocating for the total destruction of unions. But that’s obviously not what he said. Barro was saying that certain unions should be challenged on certain issues. This does not seem like the sort of proposal that can be dismissed a priori, unless one thinks that unions are inherently destined to be right on every issue all of the time.

By the same token, maybe Lyons thinks that the critics of ICE are really just trying to inflict suffering on federal employees and their loved ones. But again, that’s an exaggeration. Wu is saying stuff like:

People are terrified for their lives and for their neighbors, folks getting snatched off the street by secret police who are wearing masks, who can offer no justification for why certain people are being taken and then detained.

Sharp words—but that’s politics! You can’t just demand that all your critics shut up to protect your favorite group’s feelings. No doubt, you probably think your favorite group is doing particularly noble things. But that’s what everybody thinks about their favorite groups! We don’t have to treat your group as uniquely immune from critique unless you give us some truly special reason, and in the absence of such a reason, it just sounds like you think your group is always right on every issue.2

The need for self-critique

If you go around asking people, “Is there any type of group that’s always right on every issue?”, you’re not going to get many “yeses.” But when it comes to our cherished favorite groups, we do often act like they’re infallible.3

This is deeply bad for three reasons.

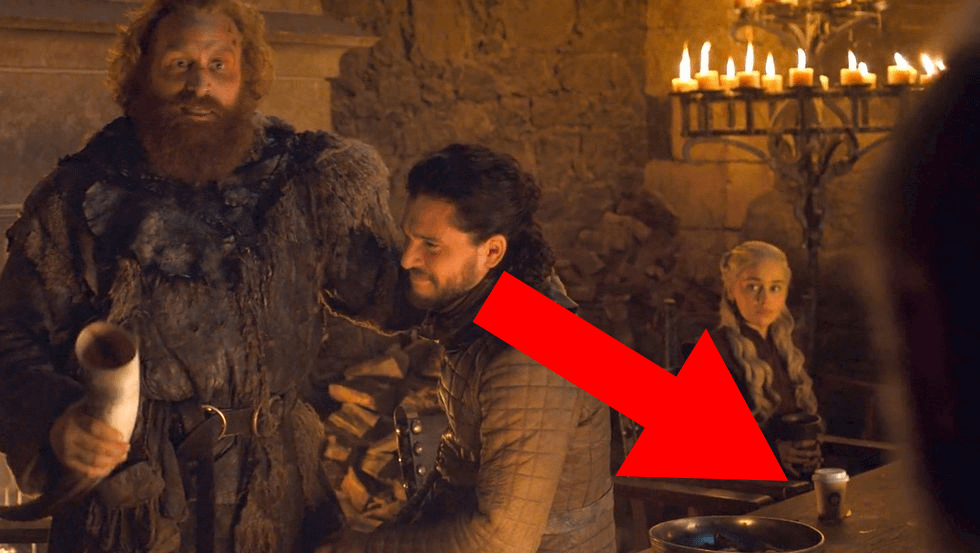

First, it’s self-defeating. We end up supporting groups even when their goals and values drift out of alignment with our own, like fans who stood by Game of Thrones through the end of Season 8.

Second, it’s bad for your favorite groups. Negative feedback, properly aimed, is indispensable for group discipline. Even the mere threat of feedback can be essential. Such feedback may take the form of “voice” (direct expression) or “exit” (taking one’s business elsewhere), and it may serve either as pure information or incentive. Whatever form it takes, feeback is the lifeblood of any group trying to maintain its effectiveness over time.4

Finally, treating your favorite groups as infallible is self-discrediting. We look ridiculous if we’re not able to call out failures on our own side.

One of the deep facts about human cooperation is that inter-group trust requires intra-group discipline. Families scold kids who bully others on the playground. Companies fire or retrain employees for bad customer service. Even prison gangs punish their own members for transgressions against other gangs, a form of violence that the scholars Toby Handfield and John Thrasher call “purification,” which they analyze as a “costly signal” that the punishing gang won’t engage in further violence.

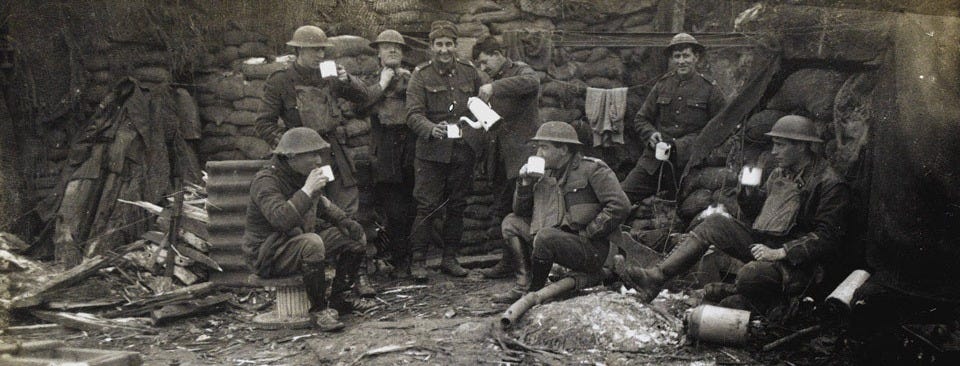

One more example, because I can’t help myself. In The Evolution of Cooperation, which I’m always referencing, Robert Axelrod analyzes the “Live and Let Live” system that broke out in the trenches of WWI, where soldiers would only pretend to target their enemies, instead bombing relatively distant areas at predictable intervals, mutually preferring this arrangement to all-out warfare. So what happened if one side bombed outside the truce? A British officer recalls:

I was having tea with A Company when we heard a lot of shouting and went out to investigate. We found our men and the Germans standing on their respective parapets. Suddenly a salvo arrived but did no damage. Naturally both sides got down and our men started swearing at the Germans, when all at once a brave German got on to his parapet at shouted out “We are very sorry about that; we hope no one was hurt. It is not our fault, it is that damned Prussian artillery.” (Quoted in The Evolution of Cooperation, pp. 84-5.)

Apologizing for the errors of one’s own side is indeed “brave.” And in this case it helped salvage an invaluable truce.

Just imagine if the Saxons had responded to the swearing Brits by saying, “Our hard-working officers are keeping the German people safe, and your comments are deeply hurtful to them and their beloved Teutonic families.”

The impossibility of perfection

If you’re ever tempted to think that your favorite form of institution can guarantee perfection, ask yourself two questions.

First, why does this institution behave so well? Usually, the answer is that the institiutional form creates opportunities for effective negative feedback. A co-op gets feedback from owners and customers; a democracy gets feedback from voters on election day. Institutions of any form are “gonna have to serve somebody.” Which group they serve is determined by which complaints they have to listen to. If complaints never get heard, don’t expect good service.

Second, what goals does this institution have? Usually, there isn’t a single overriding objective. There are multiple constraints, multiple values, multiple hungry mouths to feed. As a result, institutions run headfirst into the paradoxes of aggregation, which basically show that there are always tradeoffs involved when you want to combine multiple goals into a grand unified telos. The most famous such paradox is Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem, the proofs of which are a bit intimidating if your math is rusty, but the concepts of which are so pure and beautiful that they can be explained in monosyllables:

The upshot is that it’s hard even to formulate a coherent group objective, much less maintain one. To keep a group on track therefore requires constant vigilance—which means a neverending need for energetic feedback. Which you’re not going to get if you expect people to be your pliant little puppets.

A solution everyone will love

The moral of the story, of course, is that more substackers and government officials should read my blog, which will teach them about the challenges of designing social institutions given the reality of dispersed knowledge and the impossibility of perfect aggregation. Indeed, every schoolchild in the country should be assigned the entire Big iff True archive.

Got a problem with that? Keep it to yourself! We bloggers are real people—with real families—and frankly, I find your negativity very hurtful.

A more serious version of the argument would have been narrowly aimed at certain types of criticism and protest—e.g. burning Waymos or calling for violence. There is, of course, nothing wrong in principle with trying to distinguish illegitimate from legitimate criticism while decrying the illegitimate kind. But Lyons did not bother with such distinctions, instead portraying all criticism of ICE as unacceptable and “dangerous.”

In a recent article on the nature of political power, Ezra Klein got it exactly right:

A lot is lost when you collapse the complex interests of politics into a simple morality play. There are often different corporations on different sides of the same issue. There are often different unions on different sides of the same issue. To know where you stand — and who stands with you — you need to know what you are trying to achieve.

I’ve got a longer article on “systemic critique” coming later this year, inspired by Joe Heath’s work on co-ops and Elinor Ostrom’s work on communal vs. private property.

I have to shout out G.A. Cohen on the German Idea of Freedom, a paean to the sort of tyranny beloved by certain intellectuals.

No greater freedom can be imagined for a man than absolute, blind submission to an unjust law.

The text doesn’t really do justice to the bug-eyed, ALL CAPS delivery. RIP, Gerry.

One of Elinor Ostrom’s design principles (for successful resource-management institutions) is the use of graduated sanctions. If you want your fishery to last, there has to be some negative consequence when people fish outside their assigned spot. But you don’t want to throw the book at first-time small-fry offenders. Verbal feedback—a warning, a complaint—is often the ideal slap on the wrist.

During the "phony war" in 1940, a British soldier was told "don't shoot at the enemy, they might shoot back!"

But, less critically, I think your point about intra-group discipline extend to points about trust. For example, public health proclamarions during COVID were made with the appearance of certainty, but then changed, which make the establishment look untrustworthy. Better for trust, in my opinion, to be upfront about the possibility or chance of error than portray yourself as certain and then be wrong.