Stop blocking everyone!

Conformist parrots have diminishing returns

On June 18, Vice President J.D. Vance joined Bluesky, where he quickly set the record for most blocked account. Bluesky—the lefty 𝕏—has over 30 million “users” and 1 million daily “likers.” 110,000+ blocked the VP almost instantly.

What earned Vance his blocks? See for yourself:

Of course, you might say the VP is trolling. That he’s just pretending to want “common sense political discussion,” that his intentions can be safely assumed to be malign, that there’s no point in engaging with him—or with anyone else on increasingly popular “block lists.”

But just two days before Vance’s Bluesky debut, Rep. Sarah McBride (D-DE) struck a different tone, encouraging progressives to meet the other side with grace and to aim for persuasion rather than “purity.”

I think grace in politics means…creating room for disagreement: assuming good intentions, assuming that the people who are on the other side of an issue from you aren’t automatically hateful, horrible people. …

One of the problems we’ve had is that we’ve gone from: “It’s not my job as an individual person who’s just trying to make it through the day to educate everyone” — to: “No one from that community should educate, and frankly, we should just stop having this conversation because the fact that we are having this conversation at all is hurtful and oppressive.”

This message is all the more remarkable because of the source. It’s not coming from a centrist pundit or the Slow Boring comment section. It’s coming from the country’s first openly transgender Congressperson.

So who’s right? The Bluesky blockers, or the Delaware Democrat?

Broadly speaking: I side with McBride.

But let me admit that there are legitimate arguments for blocking, and context matters. Sometimes blocking is a good way to deny legitimacy to nefarious or incompetent actors. Some people really are trolls, spammers, and clickbaiters, and some content really is lazy, boring, trashy, and irrelevant. I’m not here to tell you otherwise, or to ask you to share my reading tastes. I’m not even here to weigh in on this particular Bluesky brouhaha—only to issue a warning.

If your goal is to get an accurate view of the world, you shouldn’t block people just for being wrong on some issues, even if those issues are deeply important to you. In fact, it’s often better to follow a less reliable source rather than a more reliable source, even when they’re talking about the same topics at the same level of detail. This bizarre fact starts to make sense once you’ve spent a little time pondering the “Condorcet Jury Theorem,” a stone-cold classic in probability theory. But let me start with a warm-up fact, which is that you should never block someone for always being wrong.1

The godlike power of always being wrong

Last December, Nathan Robinson put out one of his trademark hits in Current Affairs:

Taken literally, this is exactly the kind of argument I’m warning against. Robinson is saying that Yglesias is often wrong—indeed, always wrong—and therefore “ought to be permanently disregarded.” Of course, it’d be hard to show that Yglesias is wrong about literally everything.2 But suppose he is. Should you block him?

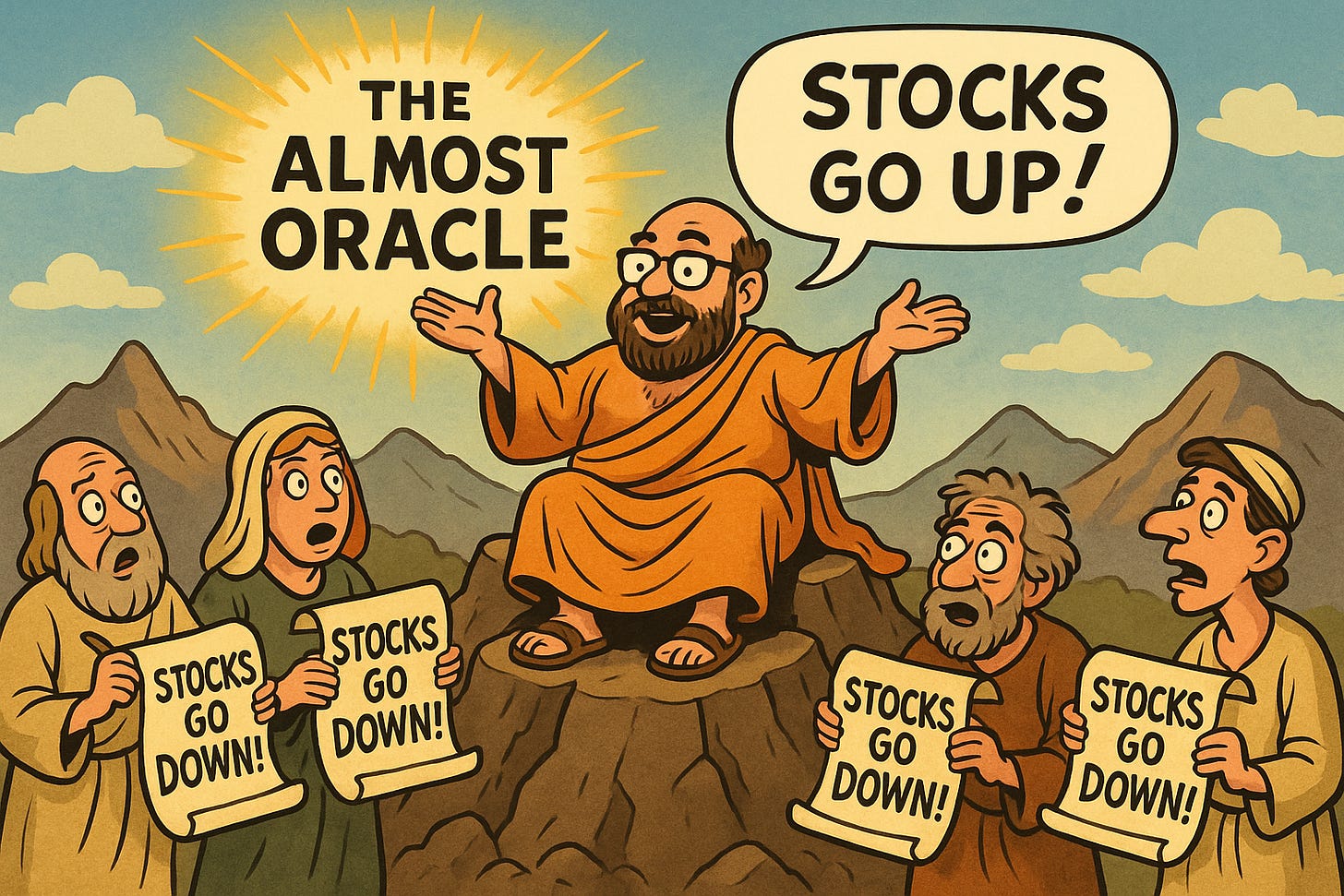

Definitely not. If Yglesias is talking about important stuff, and you know he’s always wrong, he is a priceless oracle, and you should be willing to pay almost anything to hear what he says.

Well, slight correction. He is almost an oracle: you have to add negations.

If Yglesias says that stock prices will rise, you know it’s time to sell. If he says it’s sunny outside, you know to bring an umbrella. If you’re into math, philosophy, and science, you could ask him about all the deepest unsolved problems in the world and finally get definitive answers. Does the Riemann Hypothesis hold? Does God exist? How do we harness nuclear fusion? Do the numbers count?!3

In order to be wrong in literally every case, Yglesias would still have to be extremely sensitive to the truth—just in the wrong direction. That’s why a savvy listener could use him to figure out the truth for themselves. More generally, a source with a known bias is just as good as one that is known to be unbiased. This is true for the Almost Oracle as well as for fast watches and skewed compasses.

This brings us to a supremely deep fact about epistemology: the value you get from an information source depends on what other information you have. What you get out of your source doesn’t just depend on them—it depends on you.

The marginal revolution in epistemology

Speaking of you, I’m going to bet that you probably follow multiple sources of information. (Not even counting Big iff True.)

This fact has deep implications for how you should think about the choice to block. When you hit Block, Play, or Subscribe, you’re not making an all-or-nothing choice about the totality of your information diet. You’re making a choice at the margin. You’re asking yourself, “What does this add to what I’ve already got?”

I can’t emphasize enough that this is fundamentally different from asking, of some particular source in isolation, “Is this reliable?” or even “Is this good?”

Think of the epistemologist Alan Goldman on rumors:

Rumors are stories that are widely circulated and accepted though few of the believers have access to the rumored facts. If someone hears a rumor from one source, is that source’s credibility enhanced when the same rumor is repeated by a second, third, and fourth source? Presumably not, especially if the hearer knows (or justifiably believes) that these sources are all uncritical recipients of the same rumor. (99)

When rumors rebound in an echo chamber, that does nothing to “enhance” their credibility, because the echoers are all “uncritical recipients” of the same recycled information. The second rumor-monger may be just as reliable as the first, but only the first has any marginal value.

Or consider Goldman’s guru, who we can imagine is right about everything:

Whatever the guru believes is slavishly believed by his followers. They fix their opinions wholly and exclusively on the basis of their leader’s views. Intellectually speaking, they are merely his clones. (98)

Notice that being called a “clone” isn’t just an insult—it’s also a compliment! If the guru is hyper-reliable, then so is the clone. That means the clone alone is as good as the guru alone. The trouble only starts if you fool yourself into thinking that you’re getting more out of following multiple clones. If you’ve heard one, you’ve effectively heard them all.4

This should all look topsy-turvy. The Almost Oracle is wrong about everything. The guru’s followers are right about everything. And yet, the Almost Oracle is invaluable as a resource, and the guru’s followers are worthless. (At least, they’re worthless to anyone who’s already got a line on the guru.) But strangeness is to be expected here. Now that we’re talking about the marginal value of following more sources, we’re in the realm of aggregation. Rather than comparing sources pairwise, we’re comparing combinations, which has a way of confounding our puny monkey brains—hence the Repugnant Conclusion, Simpson’s Paradox, Taurekianism, and Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem.

Do we just need dissenters?

If the problem is redundancy, the solution seems obvious. We just need to diversify our epistemic portfolios. By following more people who disagree with our current sources, we can pop our filter bubbles and escape our echo chambers. The key, it seems, is to find some contrarians. “Societies need dissent,” as Cass Sunstein once put it.

But this won’t really help. There’s nothing particularly valuable about contrarians!

We can show this with a spin on the guru case. Imagine that, instead of having followers who completely agree with him, the guru has anti-followers, who completely disagree with him. The anti-followers say exactly the opposite of what the guru says. When the guru opines that p, the anti-followers dutifully insist that not-p.5

The anti-followers are perfect contrarians, but this actually makes them just as redundant as the ordinary followers! Once you’ve heard the guru say it’s raining, you’ve effectively heard the anti-followers say it’s not raining. There’s no added value in following the contrarians once you’ve heard the original guru, or once you’ve already heard one of the other contrarians. In fact, they’re even redundant if you just follow one of the original followers.

As you can tell, I’m idealizing a little bit with these examples, assuming you know that:

There are no errors in transmission, either from guru to follower or from follower to you.

The followers are totally uncritical, never filtering any information they transmit.

The followers are comprehensive, transmitting all and only the signals they receive from the guru.

But relaxing these assumptions would only make things messy and obscure the key insight, which is that followers—and equally, anti-followers—don’t add any value as such. Once you have one source in the guru’s ecosystem, you’ve effectively got them all, and there are no true “second opinions” to be found, either among his loyal following or his disloyal dissenters.

How to add epistemic value

What would it take to get a true second opinion?

By this, I mean an opinion that actually adds something to the opinions one already has. What kind of source adds fresh value to your information diet, rather than pointless parroting or meaningless noise?

Well, one obvious way to get more value is to follow a source you know to be more reliable than your current sources taken together—a guaranteed gain. Instead of following the Flat Earth Society, just get your physics facts from Sean Carroll.

But what if you already follow the most reliable source on offer. Now what? Can anyone add any more value? We’ve already ruled out “slavish followers” and mindless contrarians. Who’s left?

You want an independent expert.

An expert, in our generous sense of the term, is anyone who’s more likely to be right than wrong. An independent source is one that isn’t screened off.

Imagine your doctor runs a test that indicates you have Disease X. You want a second opinion. So you go to another hospital, where a different doctor runs different tests, which also indicate that you have Disease X. If the two doctors’ tests are independent, then having both tests gives you better evidence that you have the disease. By contrast, if the second doctor’s test was dependent on the first, then it wouldn’t give you any additional evidence. The second doctor would be a mere “follower.”

The way to spell this out is with probabilities. If the second doctor’s take is totally dependent, we say that it’s screened off by what the first doctor says. The probability you have Disease X, given what the first doctor said, is not changed by what the second doctor said.

You don’t really need symbols to get the point, but here’s one way to symbolize it:

P(X | D1) = P(X | D1 & D2).

Where P(A | B) means “the probability of A given B,” “X” means “You have Disease X,” and “Dn” means “Doctor n says you have Disease X.”

By contrast, if the second doctor is reliable and independent of the first doctor, then we have:

P(X | D1) < P(X | D1 & D2).

But again, the point is perfectly understandable without any formalism. The point is just that independent experts add something to what you’ve already got, because they track the truth in some new way.

When you have a bunch of independent experts, it’s a fact that they tend to do better together than any one of them can do alone. The Condorcet Jury Theorem is the classic result here. It says that, if you have a group of independent experts (even if each is just barely over .5 reliable), your chances of being right if you just defer to the majority of the experts approaches 1 as the number of experts approaches infinity. This particular theorem is, in some ways, unwieldy, with its invocation of the infinite and its misleading name. (Juries deliberate together, which tends to make the jurors dependent on one another!) Still, got to pay respect to the classics.

The value of independence

At last, we can show why a less reliable source might nevertheless be more valuable.

Imagine you have three doctors to choose from. Doctor 1 is highly reliable; Doctor 2 is equally reliable but totally dependent on Doctor 1; and Doctor 3 is less reliable but still an independent expert. You’ve already heard from Doctor 1, who says you have Disease X. But you only have time to get one more opinion. Should you ask for Doctor 2, or Doctor 3?

The answer, of course, is Doctor 3—even though Doctor 2 is more reliable!

If Doctor 3 diagnoses you with Disease X, that boosts the probability you’ve got it. But if Doctor 2 diagnoses you with Disease X, that won’t teach you anything at all. (Indeed, the diagnosis is completely predictable.) Again in symbols:

P(X | D1) = P(X | D1 & D2) < P(X | D1 & D3).

Now, what if Doctor 3 disagrees with the diagnosis? Then hearing the third doctor will reduce the probability that you have the disease. This is a consequence of an underrated deep fact in probability theory. If A is evidence for B, then not-A is evidence against B. Symbolically:

If P(A | B) > P(A), then P(A | not-B) < P(A).

I like to think of this as the “No Risk, No Reward” principle of epistemology. If a certain source has the potential to support your position, it must also have the potential to undermine your position, if only to some extent. (Not always the same extent! If your friend tends to sugar-coat his fashion advice, he’s never going to give you strong evidence that your outfit is a winner. But if even he says your outfit is terrible, go change!)

The only risk-free sources of evidence, it turns out, are those sources that can’t be evidence at all—sources that are independent not of each other, but of the truth. Suppose I flip a fair coin, and it lands heads. This outcome has no bearing whatsoever on my health, the weather, the next winning lottery numbers, or the future of the economy. The “unconditional” probability that inflation will rise is exactly the same as the probability of inflation conditional on the coin landing heads. So any wannabe guru who just flips a coin to decide whether to answer “yes” or “no” will be completely uninformative.

Being truly uninformative is possible—but it’s less common than you’d think.

Back to blocking

Let’s put this all together and draw some morals about when to block and when to follow. (Again, bearing in mind there are other reasons for blocking, context matters, etc.)

If you just want one source, go with whoever’s most reliably tracking the truth.

If you’re adding more sources at the margin, look for something more truth-tracking than what you’ve got.

If that fails, look for something independent but still truth-tracking.

“Tracking the truth” doesn’t have to mean “unbiased.” If you know a source is biased towards the false, then it’s just as good for you as a source you know is biased towards the true, since you can easily correct the bias.

The only sources that are truly uninformative at the margin are those that are either (i) totally dependent on information you already have, or (ii) totally independent of the truth. This isn’t a partisan blog, so I try not to opine in general terms about high-profile politicians. But I will echo my colleague Alex Worsnip, who reminds us that even in our highly partisan climate, it’s rare to find that our opposition is truly no better than chance. If I learn that someone on the other side agrees with me about some issue, would that really make me less confident in my view? Usually, we think agreement is at least some reason to be more confident—in which case, we’re forced to conclude that disagreement is a reason to be less confident. (No Risk, No Reward!)

Now then, let me conclude by flipping the question around. We’ve been asking about when to follow a source. But you’re not just a consumer of information: you’re also a producer. What can you do to make your output more valuable at the margin for your audience?

A few tips:

Answer fresh questions, where you’re less likely to be redundant. This is why I love writers who include details, detours, stories, and stats—these add value beyond an overall take.

Say something unexpected, which can get the audience to rethink the information they already have, or to notice things that were hiding under their noses.

Show your independence, whether by citing rare sources, highlighting disagreements, or approaching from a different angle.

As for what not to do:

Don’t hide your biases. If people know where you’re coming from, they can correct for that, which makes you more valuable for them.

Don’t be a parrot (or a contrarian). You want your takes to have independence, which is more about how you get your opinions than which opinions you have.

Don’t be random. The goal is to track the truth, ideally very strongly, and ideally in some way that sets you apart from the pack.

These are all tips for the mutual benefit of you and your audience.

This last one’s just for the audience. Some practices can reveal that you’re less valuable as an information source—but in an honorable way. Citing your sources can show that you’re more of a parrot than your audience thought. Explaining the limits of your expertise can induce your audience to trust you less than they would have. As a deontologist, I think we owe it to each other—and to ourselves—to be honest even when it hurts us. And in the long run, it’s probably not a good idea for the healthy functioning of society if we’re all relying on unreliable sources, or if slavish followers are being treated like sui generis gurus.

Objection:

But I never block people just for being wrong. I only block bad faith actors. It just so happens that the overwhelming majority of people who disagree with me about [Contentious Issue] are arguing in bad faith.

Two-Part Reply:

That’s suspiciously convenient.

People can be informative despite having biases and ulterior motives. Tobacco lobbyists are nobody’s idea of a “good faith actor,” but when even they concede that cigarettes cause cancer, that’s powerful evidence of a carcinogenic effect. (My point isn’t that you should hang on their every word—only that you shouldn’t be too quick to infer from “Bad Faith Actor” to “Block, Baby, Block!”)

Note that (2) is actually going further than Rep. McBride’s call for grace. She’s right that we shouldn’t be too quick to cry “bad intentions” in a debate. But my point is even if we know the other side has bad intentions, we might still be able to learn from them.

I myself didn’t find Robinson’s arguments convincing. See Bentham’s Bulldog for objections. And note that Yglesias, to his credit, keeps himself honest by making probabilistic predictions every year and reviewing them for accuracy (2022, 2023, 2024, 2025). I wish more writers would do this!

Remember: never ask an always-wrong oracle, “Is your answer to this question false?”

By the way, there’s often an advantage to following “gurus” directly: you no longer have to keep track of how reliable the followers are. For example, if you read primary sources rather than secondary sources, you don’t have to waste time adjusting your worldview when it turns out that the secondary sources may have garbled something.

For more on gurus, followers, and saving precious time, check out my “Defeaters and Disqualifiers” (Mind, 2019), which has a reasonably funny intro. One of these days, I’ll finish the sequel, if only because I like the title. (“A Plea for Redundancy: A Plea.”)

For you negation nerds out there, by “opposite” I mean contradictory. The “contradictory” of a proposition like “It’s hot” is the negation of the whole proposition: “It’s not the case that it’s hot.” A “contrary” of this proposition, however, is something logically stronger, like “It’s cold.” Being cold rules out being hot, but it also rules out being in the middle of the temperature spectrum. (Thus hot and cold are “polar contraries.”)

The classic source here is Larry Horn’s A Natural History of Negation, which starts with a wonderful discussion of Aristotle’s logic and term-negation. (My favorite quote, as best I can remember: “Even where I depart from Aristotle, it is in his steps that I not-follow.”) But more recently the Harvard philosopher Selim Berker has come up with arguably the clearest and most authoritative treatment of “opposition” in history—though it’s buried in a paper on the ethical concept of “fittingness.” Not very fitting, Selim!

This is a bit of a nerdy quibble, but worth bringing up: our qualitative idea of an "independent" expert and an "independent" test aren't the same thing as probabilistic independence. We think of an independent expert as something like: an expert who examines the evidence without consulting the opinions/notes of other experts before forming their opinion. But that doesn't guarantee probabilistic independence. In fact, most expert judgments will be probabilistically related when looking at similar evidence sets or when operating in the same "universe of discourse," where e.g. "Martian Fish" is never going to be the correct answer.

That doesn't undermine most of your point here, which I think is more right than wrong (especially about the value of counter reliable sources; there are specific people whose social media I check because I knew they tend to be anti-correlated to the truth). But while Condorect gives some conditions under which diversifying your evidential influences can improve things, they're not conditions we often find ourselves in.

I think I have a weird extension of this logic. I sometimes deliberately keep myself ignorant of a topic, in order to leave more space for originality and potential new insights and avoid just adopting others opinions (and it's also more satisfying to figure things out for myself). I suppose I'm choosing to be less informed, in order to (hopefully) be more informative. I guess effectively trying to be the less reliable "independent expert".

It's counterintuitive that the less reliable expert might be more informative, but it's even weirder to think it might be worth choosing to be less reliable/informed yourself.

Although I tend to only do this temporarily and then try to learn what others have found after.