I was once at a New Year’s Eve Party with a bunch of moral philosophers (self included) when I said something that, apparently, struck my friends as very funny—though to be honest, I barely remember saying it.

We were a few drinks deep into the classic debate between consequentialists and deontologists. Consequentialists (as the name suggests) think you should always bring about the best consequences. Deontologists (who need a better name) think it’s wrong to bring about the best consequences if you’re violating someone’s rights. Even to save five lives, you can’t just push a guy in front of a runaway trolley.

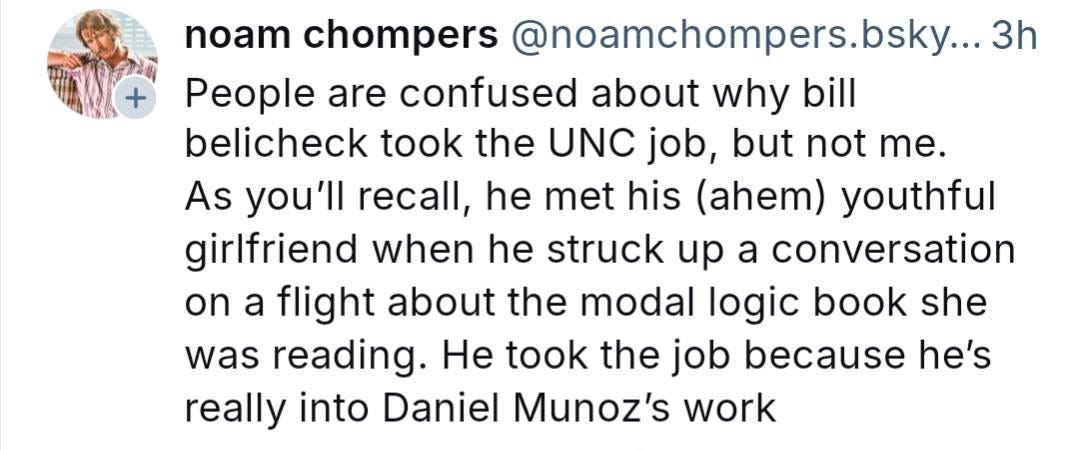

The stereotype is that consequentialists are cold-blooded calculators while deontologists are sentimental squishies. I’m a bit of an unusual case—a deontologist who loves formal methods. This peculiar mix, according to credible speculation from one of the foremost linguists posters of our time, may even have influenced the course of sports history.

But I’m getting distracted.

❤ RIGHTS

Back at the party, with the New Year approaching and the champagne disappearing, my friends Zoe and Jordan were pelting me with questions about deontology. My kind of party. Then, at some point, I’m told I stopped in the middle of a sentence, paused for a little while, looked down, put my head in my hands, and said in earnest, “I just love rights so fucking much.”

Jordan and Zoe were so amused by this silly little moment that they decided it should be commemorated. The next time I saw Jordan—who happens to be quite the ceramicist—she surprised me with a memento, a mug that says RIGHTS with a ❤ around it. I still use that mug to this day.

In fact, I’m using it now.

Lovey-Dovey Ethics

Why would this ❤-y mug mean so much to me?

To be honest, I’m not the most qualified person in the world to answer this question. My style of ethics is typically on the drier side: I’m no Kieran Setiya or Quinn White—modern masters of Lovey-Dovey Ethics. (See also: Iris Murdoch.)

But in the Tokieda spirit, I’ll venture a guess. I think the mug has higher-order symbolic value. It’s a symbol of a bit of knowledge, itself symbolic of a gift of attention, bestowed upon a distinctive characteristic of minor significance.

It’s a sign that someone cared enough to notice the little things.

The value of knowledge

Backing up a bit: like most ethicists, I think knowledge can be intrinsically good. That means it can be good to know facts about history, mathematics, art, philosophy, etc., and not just because such knowledge comes in handy. (In fact, it’s often still good to know such things even when that knowledge has negative effects, like when you feel distressed after reading about disturbing historical events.)

What makes knowledge good? Obviously it can’t just be the sheer quantity of stuff known. There’s not much value in knowing random boring data points, like the exact number of bricks in the building next door. Nor is there much value in memorizing disconnected specks of trivia.

W.D. Ross and his followers thought the best things to know were general principles concerning fundamental matters, since these have more explanatory power.1 That certainly beats the “more tonnage of knowledge = better” hypothesis. But it also suggests a fishy hierarchy, as if it were always better to know principles of “fundamental” subjects (physics, chemistry, metaphysics) rather than details of “superficial” ones (economics, psychology, history, literature). The counterexamples generate themselves: compare the knowledge you get from memorizing Newton’s laws to the grasp of human psychology you get from deeply reading Jane Austen, Frederick Douglass—or for that matter, a good psych textbook.

But let me share with you another type of counterexample, inspired by remarks from Nomy Arpaly and Tom Hurka.2 It’s intrinsically good to know things about your lover or spouse: their aspirations, music tastes, favorite foods, least favorite foods, pecadilloes—even just their birthday.3

Now, unless you are legally married to the universe, your spouse’s birthday is not a matter of fundamental cosmology. But it’s still better if you know it—and not just for the sake of timing your gifts and parties. The knowledge is good intrinsically.

Here we meet a puzzle. Why should it be intrinsically good to know something as cosmically puny as a single human’s date of birth?

Because: that bit of knowledge reflects the fact that you’re paying specific attention, which you’re presumably doing because you love a certain valuable being. Love has something like the ethical Midas touch. Whatever flows from it also tends to have symbolic value of its own.

This smacks a bit of Hurka’s “recursive” theory of goodness, inspired by G.E. Moore. On this theory, some things are plain good or bad, independent of attitudes. But then when favorable attitudes—love, attention, approval—are taken towards good things, they themselves become good. You can end up with a totem pole of lovely attitudes. That piece of art is good. So it’s good that you love it. So it’s good that I love that you love it. So it’s good that you love that I love that you love it—etc. This is the sort of thing that led Moore, cheered on by admirers in the Bloomsbury Group, to say that the highest goods in life are the “appreciation of beauty” and “pleasures of social intercourse.” Not surprised the novelists liked that one!

One qualification, though. Knowing your loved one’s birthday isn’t strictly speaking an instance of loving the good. It’s more like a side-effect. The knowledge “resonates” with the value of the love that caused it rather than “recursively” stacking on top of other lovely objects.

So we’re going beyond Moore and Hurka, here—but let’s roll with it.4

Specific attention

The silly thing I said about rights wasn’t, in any cosmic sense, particularly important. But it stuck out to my friends because of what it said about me. It was an unselfconscious revelation of an unusual affection. That it struck my friends—enough for them to make a mug—means they were paying attention. Not only that: they were attending to things, however embarrassing, that were specific to me. They weren’t just taking an interest in me as an instance of some generic type.

I’m reminded of a passage in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, where Obinze reflects on the misplaced insecurities of his wife, Kosi.

Some years ago, he had told her about an attractive banker who had come to his office to talk to him about opening an account, a young woman wearing a fitted shirt with an extra button undone, trying to hide the desperation in her eyes. “Darling, your secretary should not let any of those bank marketing girls come into your office!” Kosi had said, as though she seemed no longer to see him, Obinze, and instead saw blurred figures, classic types: a wealthy man, a female banker who had been given a target deposit amount, an easy exchange.

Kosi sees Obinze as a “blurred figure,” a smeared image of a social role rather than the particular human playing the part. Obinze, understandably, “wished Kosi feared less, conformed less.” He’s pining for the kind of specific vision that you get from friends when they notice the little things, the kind of vision that makes stereotypes fall away and idiosyncrasies—like an unrequited love of moral rights—pop out.

So here’s my take.

Being a particular human, distinct from all the others, is a valuable thing.5

So, attending to someone’s particularity is valuable (in the Moorean recursive way, like loving a good work of art).

So, being struck by someone’s particularity is also a valuable thing, as a symbol of valuable attention (just as knowing facts about one’s spouse can be valuable as a symbol of affectionate interest).

So, a silly work of pottery inspired by such an event is valuable, too, as a symbol of the particular striking (just as a wedding ring can be valuable in itself as a symbol of a particular wedding).

I’m not even going to get into the game theory of gift-giving, which is an entire anthropological-economic morass unto itself. But at least we’ve got an account of the value of the gifted object: the ❤ RIGHTS mug has value because it symbolizes specific attention, which resonates with a specific concern for a lucky individual, who happened in this instance to be…me.

Wrapping up

I am, thankfully, not famous. I’m not even the most famous Daniel Muñoz—that prize either goes to a certain Colombian soccer player or a certain New Jersey-based R&B singer, aka the Latino Bieber.

But thankfully you don’t have to be famous to appreciate the gift of specific attention. Nor is DM-ing a celebrity your best option for giving such a gift.

One of the astonishingly wonderful things about getting to be alive is that you are constantly bumping into other beings each of whom has a unique perspective on the world. One of the annoying things about being alive is that you are usually too busy to notice what makes those other beings distinct. But the possibility of apprehension is always there. And when it happens—when you do notice someone’s peculiar habits, foibles, passions, and predilections—that’s something worth commemorating.

I guess what I’m saying is, next time I hear you say something embarrassing, I’m engraving it on a bowl—deadass.

As Ross puts it in The Right and the Good,

knowledge of general principles is intellectually more valuable than knowledge of isolated matters, and…the more general the principle—the more facts it is capable of explaining—the better the knowledge. Our ideal in the pursuit of knowledge is system, and system involves the tracing of consequents to their ultimate grounds. Our aim is to know not only the ‘that’ but the ‘why’ also, when the ‘that’ has a ‘why’. (pp. 147-48)

See Hurka’s British Ethical Theorists, p. 207.

From Arpaly’s terrific “Duty, Desire, and the Good Person,”

The virtuous person, when she looks at that label indicating the country in which a shirt was made, remembers whether that country has sweatshops. Typically, she also remembers her friends’ birthdays.

And here’s Hurka in “The Goods of Friendship,” critiquing Ross’s view that knowing a stranger is just as good as knowing a friend or lover, all else equal.

A psychiatrist may understand a patient’s personality as well as she understands her spouse’s, but is understanding her spouse’s not more important for her and therefore a greater good in her life? Would it not be worse if she was mistaken about her spouse than about some patient? It may be said that correctly understanding her spouse will enable her to do many other good things for him, such as comfort him effectively when he is troubled. But understanding her patient will enable her to do the same for the patient, and if the patient’s needs are greater it may enable her to benefit the patient more. It seems to me that her understanding her spouse is a greater good just because he is her spouse, or because their shared history makes her knowledge of him more valuable than an otherwise similar knowledge of someone else.

I’m reminded of Robin Williams’ speech in Good Will Hunting about his deceased wife farting in her sleep—presented as one of the “little idiosyncrasies that only I know about.” As he explains, “We get to choose who we let into our weird little worlds.”

Or we might say, borrowing an idea from my friend Pavel, we choose who can co-author our weird little stories.

Moore himself, by the way, thought of knowledge as having “little or no value in itself,” despite being “an absolutely essential constituent in the highest goods” (such as the appreciation of beauty), which “contributes immensely to their value.” See Principia Ethica p. 199, cited in Hurka’s BET, p. 206.

More accurately, the goodness of your life is distinct from that of someone else’s. By the way, this idea—that no two lives are fungible in value, even if the two people living them are qualitatively similar—has been a big if quiet theme of 21st-century normative ethics. Kieran Setiya links this idea to love and the question of whether “the numbers should count” when choosing whom to rescue. I talk about this stuff a lot. Richard Yetter Chappell shows that even utilitarians can accept it. And Chappell’s insight has roots in the work of John Taurek and Frances Kamm—both of whom are deontologists, but as Kamm points out, the part of Taurek’s view that treats people as nonfungible isn’t just the part about rights: it’s also the consequentialist part about the value of life.

Noam Chompers is slightly wrong about the circumstances of Belichick meeting Jordan: it was actually a copy of Goldfarb’s Deductive Logic that he signed for her. I only remember since I learned from and taught that book when I was a wee lad.

I like the idea of attending to someone's particularity being valuable. Fits with Moore's principle of organic unities too. Paying close attention is good if you love the person, but seems bad if you have certain other attitudes toward them (obsession, lust) or if there are certain other facts about the beloved (they don't want your attention).