Is Daniel Muñoz blind?

The climax of the Clarity Wars, in which I'm exposed as a "self-appointed graduate of MIT."

In my last post, I argued that clear writing is good. This sort of lurid, sensational claim is an example of what anthropologists refer to as “clickbait.” Naturally, the piece quickly became the most controversial thing I’ve ever written, inspiring several vitriolic replies, along with (if you can believe it) a few sympathetic comments and posts.

For instance:

Kenny Easwaran explains that “Clarity is relational,” since what counts as “clear” depends on the audience.

Bentham's Bulldog insists that “Liking Clear Writing Isn’t A Fetish, Actually!”—in an unexpected turn towards sexual ethics.

Sam Waters suggests that, sometimes, writing unclearly “actually contributes to the effect of the arguments being made,” as in Plato’s dialogues. (Or his Cave!)

The Computational Reader argues that “obscure writing can be a way of conveying a sort of raw data rather than asserting conclusions.”

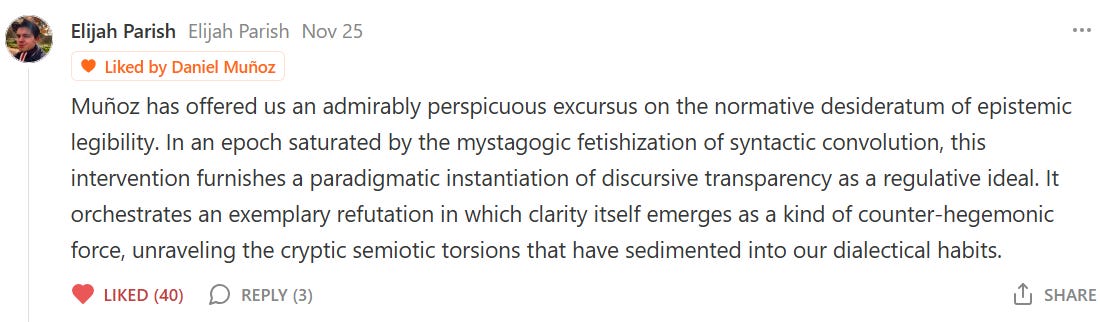

Though Elijah Parish might have taken the cake with his paean to perspicacity (refined by Linch and Felice):

That’s not all. From the ancient land of WordPress, there came shambling an article with the arresting title “What Ellie Anderson Actually Did and What Daniel Muñoz Cannot See.” Now, being Daniel Muñoz, I was immediately curious. What can I not see?

According to J. Edward Hackett, a philosophy professor in Louisiana,

Muñoz is blind methodologically to what Anderson actually did. It is not a recasting of a Butler rerun from the 90s, but a horribly embarrassing context in which a younger scholar repeats the sins of his origin.

My embarrassing sin, specifically, was that I failed to understand Ellie Anderson’s methodology. You see, I didn’t realize that Anderson was giving a “genealogical-hermeneutic argument,” which “mediates problematizing the concept clarity [sic] through Adorno.” Prof. Hackett explains:

it stands as a testament as proof in concept that Muñoz is educated at MIT to be a moral and political philosopher, but does not start with Adorno and critical theory at all. Instead, Muñoz just zooms in for what Anderson says about clarity—the concept itself, while she is involved in giving an interpretive story about how the concept ‘clarity’ came to be fetishized as explained and mediated by Adorno whose critique of ideology is well-known; unless of course, your education suffered the inherited biases of MIT’s sanctified self-image as a place that trains MIT people in social and political philosophy without reading Adorno and Habermas.

Jesus Christ—this guy does not pull punches.

Even though I am clearly down for the count, Prof. Hackett keeps it coming with the following sentence, which again exposes me as an MIT graduate:

When Muñoz picks up on her claims, he does not start thinking understanding the concept needs explained through how the concept came to be, but ultimately he thinks that someone can just focus on the claims themselves about clarity even when it is clear that Anderson has provided an interpretive basis from which she is trying to understand how clarity became fetishized in philosophized in the first place (the fact that Adorno and fetish appear together is another big hint of Anderson’s intentions, but they don’t teach Adorno in MIT’s philosophy department; notice how Muñoz avoids that very big connection).

Come to think of it…did I graduate from MIT? Prof. Hackett apparently has his doubts, referring to me as

yet another self-appointed graduate of MIT masking likely contempt for Continental authors.1

No doubt, you’ve stopped reading by now, because it’s been made painfully clear that I’m an embarrassed, blind, self-appointed graduate of a PhD program that doesn’t even make you read Adorno.2

But I will share one comment from Plasma Bloggin':

I read through the entire response looking for a single counterargument, and there wasn’t one! Most of it is him complaining about how you miss historical context, but he never says what the historical context you’re missing actually is, or how it undermines your argument. He just says you need to read more continental philosophy, and if you do, you will understand Ellie Anderson’s argument, which you supposedly misunderstand. It’s the worst version of the courtier’s reply.

And then there’s his weird disdain for MIT. He keeps bringing up the fact that you’re from MIT as if that’s a response to your arguments and complaining about how horrible MIT’s philosophy department supposedly is.

He also mentions that Anderson was trying to provide a genealogy of clarity as if this is something you missed, when in reality, this was clear, and the problem is that, as you pointed out in your post, her genealogy was wrong, pinning the concept on the correspondence theory of truth when that’s not actually why analytic philosophers believe in clarity, or a requirement for thise who believe in it.

As a newly out blind man still getting used to his phone’s text-to-speech functionality, I have to admit that I couldn’t actually read any of that comment. But I’m sure it made some fine points.

Let me also share part of a comment I left over on WordPress:

in a piece about charitable reading, I can’t help but notice that you’re speculating about my secret contempt for an entire school of philosophers. Isn’t that a bit uncharitable?3

Finally, with whatever shreds of credibility I have left, some parting advice. It’s hard not to enjoy the cut-and-thrust of internet discourse. But on the other side of all that is a human being, who probably shouldn’t be reduced to their most unfortunate posts. (We’ve all had unfortunate posts.) It’s bad to write inoffensive mush. It’s also bad to be mindlessly polemical. There has to be room for something in between—posts that are challenging without being needlessly combative or insulting, posts that leave room for an eventual meeting of the minds, if only incomplete and tentative.

“The internet isn’t real life,” they used to say. I’m not sure that’s true anymore. Our lives are ever more entangled across the unreal agora, and no one really knows how we’re supposed to cope with one another on here. Maybe the solution will look clear in hindsight. For now, I have only obscure hunches.

Happy update:

J. E. Hackett has written a reply, “Muñoz’s Ignoring of Actual Arguments,” and despite what that title might suggest, I think we managed to reach an amicable conclusion over in his comment section.

Update: it turns out that this was, as you’d guess, just a typo. In a follow up, Prof. Hackett reports that the phrase was originally meant to be “self-appointed sanctimonious ass.” (Which is both more insulting and less funny. I prefer the typo, personally!)

For the record, I don’t think Prof. Hackett meant to insult people who are literally blind.

[Petty footnote deleted for civility reasons.]

On behalf of Professor Hackett, I’d like to challenge you to a formal, moderated debate about whether you actually graduated from MIT.

In the comment thread under Hackett’s post, the best argument you could muster was that there are pictures of you in a cap and gown. Assuming that those pictures havent been digitally manipulated (I consulted with Bart Sibel and he says that Google’s SOTA image classifier has determined there is strong evidence they have been), there are tons of alternative explanations for that data.

Meanwhile, the theory that you graduated is absurd:

(1) - You’re telling me that you were able to graduate in 2014 and 2019 but havent done it again since? That’s very suspicious.

(2) - In the comments on Hackett’s post, you claim that you have now read Adorno. But everybody knows that an MIT graduate would never do that. So were you lying then or are you lying now?

(3) - I’ve constructed a critical-intellectual genealogy that would go way over your head - rest assured, it definitively establishes that there is no way that you graduated from MIT.

If you accept the debate, I will use these and many other arguments to expose the ‘self-appointedness’ of your pretensions to be an MIT alum. Shame!

To be honest, the most demoralizing part of this whole discourse cycle has just been the extent to which people are willing to lob around completely philosophically inert insults at one another. I am currently drafting a post about this, but why is it that we feel the need to call one another illiterate or blind or what-have-you, rather than just explaining why we disagree? I am all for being direct, but I think that 90% of the time, observing good manners actually allows us to be more direct in our critiques, rather than less, since it doesn’t muddy the waters of the discussion. As a bonus, it will probably make it more likely that the other person will actually take them on board