The Lightbulb Has to *Want* to Change

Before Wittgenstein's fly-bottle, there was Hobbes' false light. Are we still trapped?

The Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein had what some literary theorists call “good words.” His Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus begins: “The world is everything that is the case.” Its final proposition is even more arresting: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Culture and Value, drawn from Wittgenstein’s notes, glitters with timeless bon mots—“No one can think a thought for me in the way no one can don my hat for me”—amongst some grubby disses. (“Mendelssohn is not a peak, but a plateau. His Englishness.”)

The pinnacle, at least for me, arrives in Wittgenstein’s posthumous Philosophical Investigations. It is here that we find the most stylish parenthetical remark in all of philosophy, from §308.

(The decisive movement in the conjuring trick has been made, and it was the very one that we thought quite innocent.)

But §309 may be even better. Here it is in full:

What is your aim in philosophy?—To shew the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.

I’m hardly the only §309 fan. It’s deservedly one of the most famous lines in 20th-century philosophy. But it is also widely misunderstood. I’ve heard people say they love the quote, but then when asked, “What’s a fly-bottle?” they’ve confided in me that they don’t really know. A bottle, I guess? And you put flies in it? And the flies are philosophically confused for some reason?

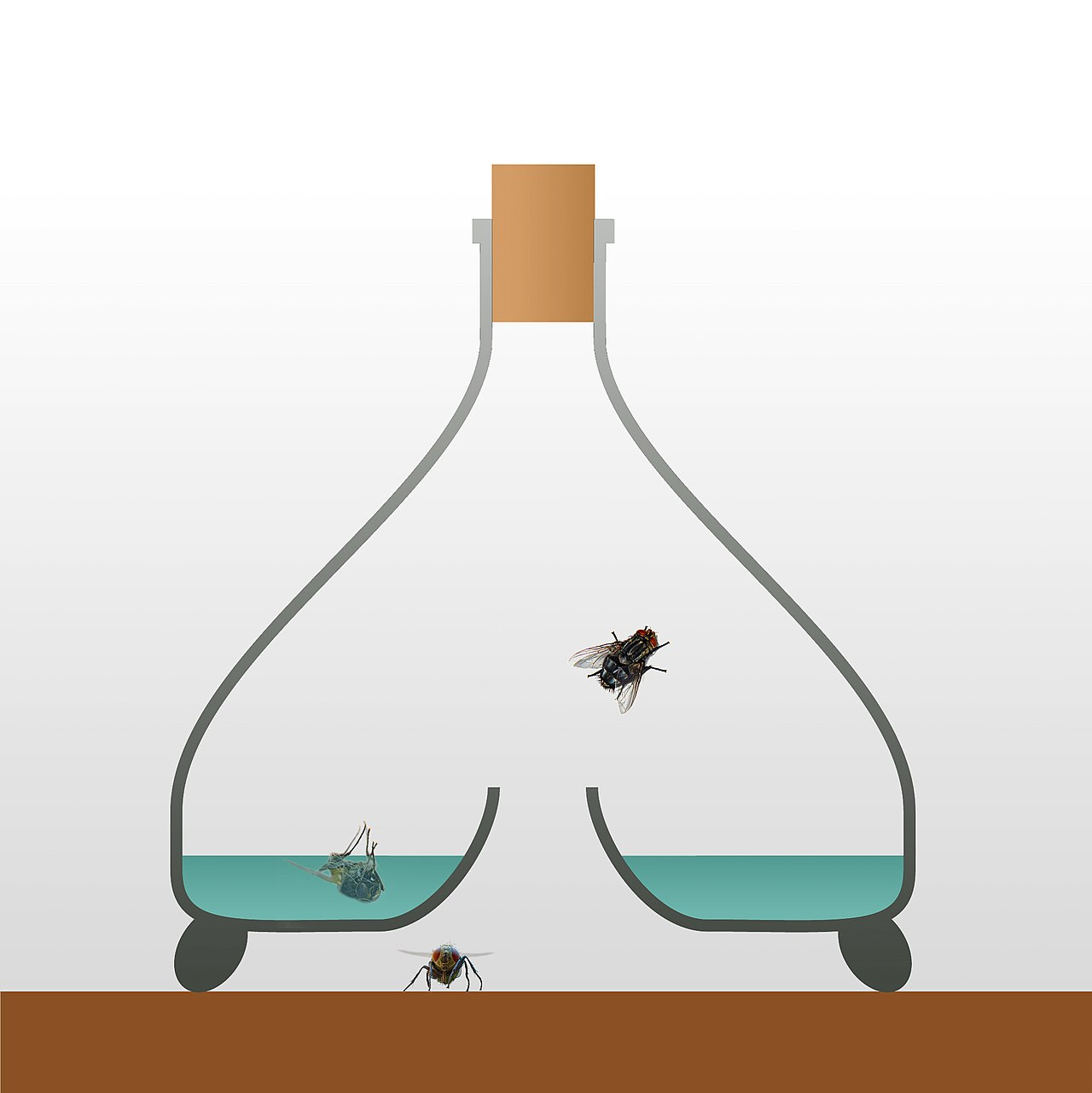

This is understandable. Not many people these days use fly-bottles. A fly-bottle, since you asked, is very different from a soda bottle or water bottle. (It’s not even homeomorphic to ordinary bottles!) A fly-bottle is basically a big wide jug with a hole in the bottom:

The point of a fly-bottle is not to store liquid but to trap flies—hence the more accurate name, “fly-trap.” People used to put some sugar water inside of a fly-bottle to tempt flies to enter from below. The flies, not being especially bright, would then try to leave through the top or sides. For the rest of their miserable lives, the trapped insects would beat themselves against the glassy walls of their prison, oblivious to the unguarded escape route below—even though they themselves had used this very same route to enter the trap not long before, lured in by the smell of sugar.

That’s how Wittgenstein conceived of so much philosophy—a pointless, endless struggle due to bewitchment by one’s own language. People start out with what seems like a harmless assumption about how language works (entering the bottle), then they flounder about doing non-Wittgensteinian philosophy (smacking against the glass). The solution is to undo the initial error, to leave the bottle through the bottom. You can see now why Wittgenstein did not want to present his ideas as more of the same kind of philosophy. It was instead a repudiation of a futile style of philosophy, an exhortation to leave the trap behind.

I was reminded of Wittgenstein’s metaphor a few weeks ago while doing some teaching prep. My Gateway to Philosophy, Politics, and Economics usually begins with Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, which is famous for its extremely forceful presentation of the dangers in living outside the aegis of a state. Most writers call this “the state of nature.” Hobbes calls it “the natural condition of mankind,” and he saw it as implacably hostile to any form of wide-scale cooperation, so that human life within that condition would of necessity be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Nowadays, political philosophy books are mostly about political philosophy. But Leviathan is loaded up with theology, epistemology, proto-psychology, and even proto-linguistics. These were the days when nobody thought it was weird to begin your justification of state authority by giving a theory of sense perception and (for good measure) a definition of dreaming.

One key idea from the start of Leviathan is Hobbes’s conception of knowledge. The ideal, for him, is not probabilistic knowledge about cause and effect. It is not metaphysical insight into the nature of reality. And it is certainly not moral intuition about right and wrong. The ideal is geometry—“(the only science that it hath pleased God hitherto to bestow on mankind)”, as Hobbes calls it, in another hall-of-fame parenthetical. For Hobbes, the way geometry works is that you first come up with definitions, then you observe what follows from these definitions. That’s it! You thereby come to know “a universal rule” that is “true in all times and places.” No wonder Hobbes begins his book with so many meticulous definitions. He wants to be the Euclid of politics.

But what if you’re not like the Euclid of legend, heroically coming up with every definition by yourself? What if you get your definitions from books, lectures, and various high-quality Substacks?

Then you have to be careful. If you naively trust a book with bad definitions, you will inherit the confusions of its author, and as you build up your big-picture philosophy, those confusions will only multiply. Hobbes expresses his contempt in a poignant image:

[T]hey which trust to books do as they that cast up many little sums into a greater, without considering whether those little sums were rightly cast up or not; and at last finding the error visible, and not mistrusting their first grounds, know not which way to clear themselves, spend time in fluttering over their books; as birds that entering by the chimney, and finding themselves enclosed in a chamber, flutter at the false light of a glass window, for want of wit to consider which way they came in

Like the fly in the trap, the bird that comes in through the chimney yearns for a return to freedom, but dooms itself by attempting only the most direct and simple paths. The way out is not so direct, not quite so simple. One must backtrack—revisiting first principles. One must define everything anew.

The image is unmistakably Wittgensteinian. Hobbes continues:

[I]n the right definition of names lies the first use of speech; which is the acquisition of science: and in wrong, or no definitions, lies the first abuse; from which proceed all false and senseless tenets; which make those men that take their instruction from the authority of books, and not from their own meditation, to be as much below the condition of ignorant men as men endued with true science are above it.

This “first abuse,” leading to “all false and senseless tenets,” reminds me of the “decisive movement in the conjuring trick.” In both passages there is a kind of intellectual original sin. For Hobbes, a reader is reduplicating the errors of an author; for Wittgenstein, a viewer is fooled by a magician’s sleight of hand. The element of trickery makes Wittgenstein’s metaphor more Edenic—the pre-Wittgensteinian philosopher is tempted by the fruit of philosophical knowledge, unaware of its unattainability. But both authors emphasize that the solution involves an exercise of intellectual autonomy. Wittgenstein can only “shew” the way out; Hobbes is asking you to come up with definitions for yourself. Had either asked for his readers’ passive capitulation, the argument would have been self-defeating.

Also echoing Hobbes—though this time, in form moreso than content—was Vladimir Nabokov. Here is the first stanza of Pale Fire, a text that I love too much to spoil for you any more than is strictly necessary.1

I was the shadow of the waxwing slain

By the false azure in the windowpane;

I was the smudge of ashen fluff—and I

Lived on, flew on, in the reflected sky.

And from the inside, too, I’d duplicate

Myself, my lamp, an apple on a plate:

Uncurtaining the night, I’d let dark glass

Hang all the furniture above the grass,

And how delightful when a fall of snow

Covered my glimpse of lawn and reached up so

As to make chair and bed exactly stand

Upon that snow, out in that crystal land!

The image is more complex than those in Hobbes and Wittgenstein. Is the writer, John Shade, trapped inside the glass walls—or does he truly “delight” to see his life reflected back at him? Is the man fatally deceived like the bird that crashes into his window—or does being the “shadow” mean something else, something more spiritual or hopeful?

Wittgenstein’s fly and and Hobbes’s fluttering bird lack any imagination. But the deceived philosopher, whom they represent, is obviously not so simple-minded. For this reason, I find it interesting to revisit Hobbes’ and Wittgenstein’s metaphors while bearing in mind the extra complexities of Nabokov’s imagery—fantasy, illusion, self-deception, self-invention.

This is also a nice chance to share with you one of the most underrated videos on YouTube. Here is Kathryn Haydon reciting all 999 lines of Pale Fire (plus the unmissable foreward) from memory in one take.

At the time of writing, Kathryn’s performance has only 7,242 views. But just think of the intrinsic value!

I hope you’ll forgive me for dipping into Wittgenstein, Hobbes, and Nabokov so cavalierly and briefly. These are not writers whose texts fit neatly into cute slogans, though I gather that Tractatus merch sells pretty well on RedBubble.

At the risk of further drive-by philosophizing, I am professionally obligated to mention at this point Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, deservedly the most famous metaphor for the plight of enlightenment. The Allegory, as told by Socrates in The Republic, goes like this:

Imagine some captives chained inside an underground cave, unable to look at anything but shadows cast on the walls by hidden puppeteers.

These captives would “consider the truth to be nothing but the shadows.”

The captives would not, even if freed, be able to look at the firelight without pain, and they would prefer to retreat to their captivity rathern than accept the reality of the rest of the cave.

If forcibly dragged outside, however, a captive would eventually be able to use reason and see the sun as the “governor of every visible thing.”

Even so, the former captive could not free the others. Upon returning to the dark, his eyes would take time to readjust, and—being unable to see the shadows as well as the others—he would become a “laughing-stock” rather than a liberator.

Plato’s Cave is intriguingly similar to the other metaphors we’ve encountered, but let me note a few things that make the Cave distinctive:

The captives have a little society built around the shadows, complete with shared values and norms (not just shame for the liberator, but “honors and awards” for those best at shadow-recognition). The flies and flutterers, by contrast, are deluded purely as individuals.

In addition to the comforts of the shadow-world, there is the unbearable brightness of the light. The birds are not similarly repelled by the chimney, nor are the flies turned off by the bottom of the bottle. The birds and flies are merely oblivious.

Like Wittgenstein’s conjurer and Nabokov’s John Shade (who might as well be named “Mr. Shadow”), the puppeteers are actively creating an illusion—though in Plato’s case, the purpose of the endeavor is left mysterious.

I want to close with a bit of meta-reflection. Unlike Hobbes, I don’t think there’s any scientific method for finding one’s way back up the chimney. All rational reflection presupposes some given principles, or must at least take as given some set of presumptively acceptable concepts. You cannot immunize yourself against error by starting over, shouting “It’s definition time!” and doing your best Euclid impression. Indeed, Hobbes was notorious for his blundering as an amateur geometer. (In one attempt to “square the circle,” i.e. construct a square of the same area as a given circle using only a compass and straightedge, Hobbes relied on the “fact” that π = 3.2. Yes, people corrected him. No, he didn’t take it well.)2

I am also a bit pessimistic about the idea that there is anyone who can reliably “shew” us flies the way to freedom. For one thing, even if Wittgenstein is right about the fly-bottle of traditional philosophy, there is no guarantee that this is the only trap around. We could be living inside of a fly-bottle within a fly-bottle, and for all I know, the outer bottle is something Wittgenstein never noticed, or even something that his own philosophy will actively prevent us from escaping. (“Out of the frying pan, into the fire.”)

My fear, in full generality, is that I might be living inside of a closed system of thought. The concept is clearly at least as old as Plato, but the term is from Raymond Smullyan, one of my favorite philosophers (also an accomplished “mathemugician”). Smullyan writes, in This Book Needs No Title,

One of the human phenomena I find most disturbing is that of a person whose system of thought is such that there is no possibility of his ever finding out that he is wrong—even if he is. Any rational objection to his system can be explained away by a rationalization within the system, whose validity can be known only when one accepts the very premises of the system which are in question.

Smullyan then gives a number of examples—religious groups, political factions, Freudians, etc.—and concludes:

The interesting thing is that in the majority of cases, each of the groups I have mentioned can easily see through the prejudices of the others. And surely I must be in a similar category without realizing it. I wonder what my prejudices could be?

Smullyan stops there, but a natural next thought is that wondering itself might deliver us from closed systems. How else are we to find the chimney? To remember the hole at the bottom of the bottle?

(It is also worth wondering: should we distinguish inescapable systems, which one cannot possibly leave no matter how one struggles, from locked systems, which can be escaped with the help of some hidden cognitive key, if only one is creative enough to find it?)

But something about Plato’s shadows and Hobbes’s window—not to mention Nabokov’s “crystal land” of fantasy—prevents me from ending there. It’s probably not enough to wonder abstractly if one might be confined and where the exits might lie. Before one can begin searching in earnest for an escape, one must, somehow, shake off the allure of the false light, the comfort of the shadows. To put it in terms that Smullyan might have enjoyed:

How many Freudians does it take to change a lightbulb?

One—but the lightbulb has to want to change.

As in Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman, my favorite novel that I read in college, it’s best to go into Pale Fire knowing nothing about it. Even this advice may reveal too much, hence why I’ve cleverly hidden it in a footnote.

As you might imagine, I’m equally skeptical of Descartes-style meditation. It may be useful, but it’s not infallible.

Would it help us out if we try to reject the notion of "true definitions", and instead try treating all language and logic as just pragmatic tools that will always fall short of the reality beyond our concepts? So we are free to conceptualise and reconceptualise without end, so long as we understand that it's always only provisional, and remain open to seeing things from another angle.

I loved this essay. The starting comparison between Wittgenstein and Hobbes was already fascinating, but then you pulled it across so many genres! I have fond memories of reading Raymond Smullyan’s puzzle books as a child.

As for Nabokov, you’re making me think I should go and reread “Pale Fire.” It had a quietly profound influence on an essay that I wrote a while back, but only as a memory of that first reading. You’re quite right to compare it either to a trap or to freedom from one, ambiguously speaking (and I hope this is likewise vague enough for anyone unspoiled!)