“What is speedrunning?”

Speedrun.com gets right to the point:

Speedrunning is when an individual attempts to beat part or all of a video game as quickly as possible.

But you could’ve guessed that from the name.

What’s surprising is that speedrunning has become such a phenomenon. I don’t just mean “thousands of people do speedruns” (they do), or “millions of people are watching speedruns every day” (they are).

Documentaries about speedruns regularly get millions of views.

The richest man in the world, two weeks after a historic intervention into one of the most consequential elections in world history, was telling his hundreds of millions of followers about the relevatory benefits of speedrunning.

Yearly events raise tens of millions of dollars for charity. Leaderboards have evolved elaborate norms for documenting runs and delineating one type of run from another—say, “Any %” vs. “Glitchless 100%.” Speedrunning has even become a status symbol, as demonstrated by a pathetic string of online arrivistes exposed for faking runs.

This is puzzling

But as simple as the core idea may sound—play game fast—I find the entire practice of speedrunning extremely puzzling on a philosophical level. What the hell are these people actually doing?

Speedrunners, to be clear, are not playing the game like normal players. They break the game, exploiting glitches and abusing overpowered strategies to subvert the laws of the fictional universe in ways that defy easy description. Players duplicate items as if by magic, walk through walls, fall through floors, skip as much plot as possible, and zip! across the map, all the while using oddly precise techniques that have the air of arcane rituals.

Watching a speedrun of a familiar game like Breath of the Wild is like watching someone use a checkers board to summon a demon.

Nobody has done more to bring out this eldritch strangeness than Jeremy Chinshue (aka TerminalMontage), who’s racked up hundreds of millions of views with his “animated speedruns.” These videos depict a state-of-the-art speedrun as if it were a story unfolding within the world of the game. The result is a bizarre, quasi-mythological tale whose protagonist appears unworldly, inscrutable, implacable, dead behind the eyes, and, at times, possessed of godlike powers.

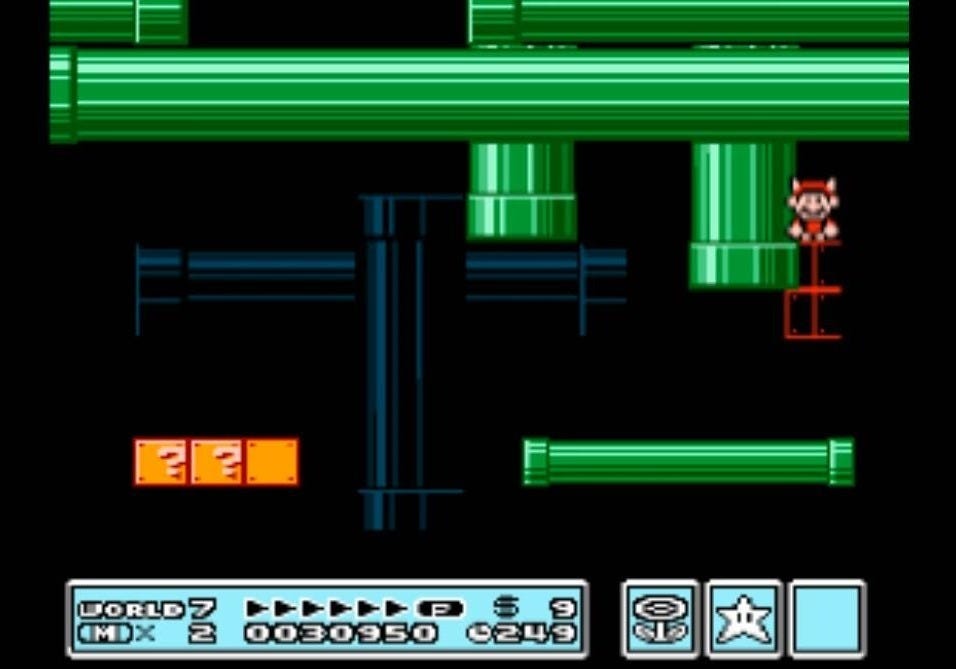

Take Super Mario Bros 3. At first, Chinshue’s Mario is tearing through the world with haste, making his way to Princess Peach. Then come bursts of static. Mario terrorizes several Koopas on his way to the top of one level, from which he impishly drops a red shell. He bounces madly back and forth across the screen, following the shell along its descent.

Suddenly—ex nihilo—there emerges an anomalous black and red box. Mario peers inside, bathed in the light of a curious portal. He enters.

He’s immediately cast into a bottomless digital abyss, surrounded by a Kubrick-esque kaleidoscope of duplications and distortions.

And then—pop—there he is, safe and sound at Peach’s Castle. A short peaceful beat, and our hero begins wildly careening and glitching as before. The Princess, understandably, freaks out, screaming as she crawls into a corner, away from the crescendo of inhumanly clipped yahoos.

Cracking the code

The joke of the video is that Speedrunner Mario is—one wants to say in reality—executing the Red Pipe Glitch, discovered by RAT926, which allows the player to Wrong Warp from World 7-1 straight to the end of the game.

This glitch involves arbitrary code execution (ACE), which means that the player has found a way not just to exploit badly designed mechanics, but to rewrite the code of the game itself. The details of how this works are so unbelievably obscure and intricate that it boggles the mind that they were ever discovered.

Just to give you a flavor:

Touching the glitch tile, an invisible note block, makes the processor try to update memory outside of the normal tile data, at an address ($9c70) that reprograms how the processor interprets addresses. This causes execution to jump to an unintended area of the ROM and execute incorrect instructions. Eventually, the stack overflows and it starts executing RAM instructions starting at address $0081, which is just before the location of the player x value at $0090 and enemy x values $0091-5.

As a reminder, we are still talking about Super Mario Bros 3.

Executing the Red Pipe Glitch turns out to require a whole series of (seemingly pointless) actions executed with superhuman precision. The SM3 image above was, indeed, not one of a human player. It was from a TAS (tool-assisted speedrun), a fully programmed run through the game—sort of like a high-tech player piano, but for Mario and Final Fantasy instead of “Für Elise” and “The Entertainer.”

But enough preamble. Let’s see why speedrunning needs a theory.

Two theories of games

The naive theory of video games is that they’re interactive stories. Rather than passively watching a fictional tale unfold, the player makes choices and achieves feats to shape the course of the narrative. The sensation of playing serves to heighten the experience.

But as we’ve just learned from Chinshue, speedruns are too weird for storytelling. Maybe normal players are crafting stories. But speedrunners clearly aren’t. (“Did I ever tell you the one about the plumber who executed arbitrary code?”) A true speedrunner has no time for character development and zero interest in plot.

A more promising theory, which better captures the role of gameplay, is that games are a kind of contrived challenge.

The classic example here is The Grasshopper, in which Bernard Suits defines playing a game as “the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” Playing a game requires:

A prelusory goal that can be described independently of the game (like “put orange ball in hoop,” unlike “score more points”).

Constitutive rules for how that goal may be achieved (like “no ladders allowed”).

A lusory attitude, which means accepting the rules in order to make the game possible (a true basketball player must forgo ladders for the sake of the game, not just because ladders are annoying to lug around).

I think there’s a lot to this definition. Certainly, it’s a revealing way to look at sports, boardgames, and various other competitions, such as the Iowa State Cow Chip Throwing Contest.

But does it work for speedrunning a video game?

Video games—like films and paintings, but unlike the Iowa State Cow Chip Throwing Contest—invite us to make-believe that we are experiencing a non-actual world, where we encounter events that may never actually occur. This raises three problems for applying Suits’ analysis.

1. The prelusory goal

First, what could be the prelusory goal of a video game—say, Dark Souls? It can’t be something defined totally without reference to the fiction, like “get the game console to be in such-and-such internal state,” or “Get the words VICTORY ACHIEVED to appear on your screen in triumphant golden text.”

The goal, I think, has to be understood in terms of the fictional world of Dark Souls, something like “save the world from darkness.”

…except that can’t quite be right, either. Without getting into spoilers, there are two distinct end-goals you might have in Dark Souls, not just one. Nor can the the goal be the disjunction—achieve this goal or that one—since the player isn’t introduced to either goal until quite far into the game. (Indeed, I didn’t even know about the second possible ending until well after beating the first.) Surely you’re playing Dark Souls from the start, no?

And besides, couldn’t you play Dark Souls without any intention of beating the game, and therefore with no overarching end-goal whatsoever?

Very mysterious.

2. The constitutive rules

As any Souls fan will interrupt your day to tell you, you haven’t really beaten Dark Souls if you cheated—e.g. by using hacks to give yourself infinite health, or by hacking your save file to get you straight to the final boss. And Suits can show us why: the game of Dark Souls has (brutal) constitutive rules set by the designers. Violate those rules, and you’re not really playing the game.

But wait a minute. Aren’t speedrunners constantly cheating? Don’t they abuse glitches and even rewrite the code of the game?

Admittedly, not always. Some speedruns are required by leaderboards to be “glitchless.” Others require “no major glitches,” “no amiibo,” or other milder constraints. It’s only in certain relatively anarchic runs where you find truly gamebreaking shenanigans.

But that still leaves glitchy Any % runs as a glaring counterexample. We still have runners who are violating the constitutive rules of Dark Souls while nevertheless apparently playing the game.

3. The lusory attitude

When glitch-abusing speedrunners violate the rules of the game, they’re obviously not accepting those rules. But it’s equally true that runners don’t accept the rules when they’re hunting for glitches, or even just hoping for glitches. The very spirit of speedrunning seems antithetical to playing the game.

At last: a theory of speedruns

The key to these mysteries, I think, is that there are really two notions of a video game. There is the game as framework, and the game as activity.1

Let me give you an analogy. What is it to play a game of cards? Well, you’re playing a game, and you’re using some cards. But obviously you could use the exact same deck of cards to play quite a lot of different games, depending on what rules and goals you accept—Poker, War, Hearts, Go Fish.

The deck of cards is the framework. Poker is the activity. And it is the activity that I suggest we think of as the game proper for the purposes of a Suitsian analysis.

If you and I both have a copy of Dark Souls, we have the same objective framework for playing. But we might be playing totally different games—i.e. different activities—depending on what subjective rules and goals we accept. If you’re speedrunning the game, whereas I’m just doing the main quest, we’re playing different games. We are merely using the same deck of cards, so to speak.

So what is the lusory goal of ordinary Dark Souls? I don’t think there’s just one mandatory goal. Some goals are certainly suggested to the player as they explore the game-world—acquire souls, level up, ring the bells, slay these creatures…—but the actual choice of what to aim for is left almost entirely up to the player. What this means is that there are many games, many activities one might discover or take up as one explores the world of the fiction. You do not just play one “game” when you’re playing through Zelda: Breath of Wild any more than you “do one thing” over the course of your day. The player engages in many related goal-directed activities—some nested, some sequential—and there are many groupings of the activities that might be said to constitute distinct games.2 Some things you do “in game” might not be games at all.

What about the speedrunner who breaks the rules of the game? They aren’t breaking the rules, so much as replacing them. The speedrunner who performs ACE to skip to the end of Zelda: Ocarina of Time is simply not playing the same game as someone who is trying to get to the castle in the usual way—just as I’m not playing poker when I use my deck for magic tricks.

Finally, what of the glitch-hunter, who lacks the lusory attitude? They do indeed lack the attitude required for runs of the plain-vanilla game. But they have exactly the right mindset for the speedrun, a distinctive game in itself.

🔥 VICTORY ACHIEVED 🔥

The speedrun isn’t a speedy interactive story—it’s not a choose-your-own adventure on amphetamines. It’s more like an athletic contest with a fictional backdrop. That backdrop certainly adds interest, but it’s not the fundamental point of the endeavor, any more than the point of chess is to conjure tales of warring monarchs.

Like any competion, speedrunning spawns communities. In their quest for speed, a community may end up discovering mechanics and mistakes hidden deep within their beloved game’s architecture. Such knowledge tends to come off as obscure to inhabitants of the real-world—and it would seem positively supernatural to anyone in world of the game. To an NPC, speedrunners must seem like higher-dimensional scientists, probing the laws of nature for loopholes. Or perhaps they appear more as Greek gods, blessing and manipulating a chosen mortal for their own enigmatic purposes.

If that sounds a bit freaky, don’t worry. It’ll all be over soon.

I’m hardly the only pluralist about games. In “The Forms and Fluidity of Game Play,” C. Thi Nguyen argues that types of game-play come in a spectrum, with make-believe on one end and striving on the other. He also argues, I think convincingly, that someone playing a video game has a choice about the basic shape of play. Nguyen believes that

game-play is fluid - that the form of play is not fixed by the game, but chosen by the player. It is up to the player of a narrative computer game, like Grand Theft Auto, whether they engage in a game of imaginative role-playing, a competitive game of scoring more points, or some mixture of the two. The presumption of the uni-dimensionality of play masks a really interesting phenomenon: that the basic form of play is voluntary and highly variable, even inside one game.

But where Nguyen says that Grand Theft Auto is “one game,” I want to emphasize that there’s an important sense in which it’s not a game at all. It’s not like Poker or Hot Potato, where the prelusory goal is pre-defined. Grand Theft Auto—the thing you can buy at GameStop—is more like a device you can use to prompt yourself to imagine a fictional world, which you then imagine yourself able to influence as the “player.” In that world, some objectives may suggest themselves. But you may also adopt your own, totally independent prelusory goal—like the speedrunner. Once you have your goal and rules, then you’ve got a game.

(By the way, “game” is far from the only ordinary noun to harbor multiple conflicting meanings. As Noam Chomsky likes to remind people, you can paint a door white and then walk through it.)

There’s also an interesting question of how we take up the goals of the game-as-activity.

In Games: Agency as Art, C. Thi Nguyen distinguishes between two modes of play: achieiving is playing to win; striving is winning to play. The difference is one of motivational fundamentality. Do we ultimately care about winning, or just the struggle?

In “Who Cares About Winning?” Nathaniel Baron-Schmitt argues that, when we play a game to win, we needn’t actually care about victory. To play basketball, we just have to make-believe that it’s important for the ball to go through the hoop, not actually take it to be of significance. (The speedrunner, on a Baron-Schmittian analysis, need only imagine that going fast matters. By contrast, for Nguyen, the speedrunner adopts going fast as an actual goal, if only a temporary one.)

In “Video Games as a New Mode of Storytelling,” an extraordinary Harvard undergradutate thesis, Aaron Suduiko argues that video games differ from ordinary stories in that the player is both passive audience and active part of the fiction. When you play a Mario game, you don’t imagine being Mario, sharing his goals and beliefs—often you know more than he does, and you may not care what he wants. You imagine yourself playing a distinctive role, what Sudioko calls the fictional player, orchestrating what happens in a deeper layer of the make-believe where characters like Mario reside. The fictional player’s goals will not in general be yours, nor must they be goals of any character. This allows for all kinds of interesting tensions, as in The Last of Us, Part II (which I once discussed with Aaron on his podcast, With a Terrible Fate). Thankfully for philosophy, Aaron’s now getting his PhD at USC, a top program.

There is an argument to be made (by people like Mark from TheElectricUnderground) that the increased interest in speedruns partially stems from the decline in score-play.

Score has been phased out of most modern games meaning that the majority of (new) games lack an objective metric for performance.

You could make the argument that score-play is a "dev-sanctioned" way to play while speedrunning promotes ruthless efficiency, but the truth is that we often see speedruns work within arbitrary restraints anyways. While scoreplay can include as many exploits as speedrunning it can also support methods of gameplay which has less friction with the core game design, which might be a good thing.

I would urge anyone who likes speedrunning to check out a high-skill run of Hyper Demon or superplay of any CAVE shmup.

It makes me think of people who "jailbreak" AI, trying to push it to go beyond its inbuilt rules.

I think the appeal of jailbreak and speedruns is often the same: pushing the boundaries of what's possible.

And I think that's roughly the essence of play: exploring possibility space for the sake of it. Normal play is within the possibility space of the game's rules, but a speedrun (or jailbreak) is exploring a larger possibility space.