Why is Elon Musk legally allowed to spend $250,000,000 on an election?

Bernie Sanders blames Citizens United, but that's just the tip of the iceberg

One meme that just won’t die is that Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, decided by the Roberts Court in 2010, is the worst thing ever to happen to American political campaigns—the original sin of a fallen democracy.

Reddit is full of threads like the following:

And X is full of…I guess we still call them “tweets”…like these:

Last year, Bernie Sanders even took this message to the DNC:

My friends, at the very top of [our] To Do list is the need to get big money out of our political process. Billionaires in both parties should not be able to buy elections, including primary elections. For the sake of our democracy, we must overturn the disastrous Citizens United Supreme Court decision and move toward public funding of elections.

Soon after, Truthout misreported this part of the speech:

Sen. Bernie Sanders said during his primetime appearance at the Democratic National Convention Tuesday night that overturning the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision should be “at the very top” of the party’s list of priorities…

Sanders, to his credit, didn’t say the priority was overturning Citizens United. He said it was getting “big money out of our political process.”

But it’s a bad sign for our political discourse that Citizens United so often serves as a synecdoche for the broader problems of money in politics. Repealing Citizens United would be a superficial change, with little effect on the true pathologies of American campaign finance.

The legitimate complaints against Citizens United—that money shouldn’t be speech, that the law should be able to limit billionaires’ campaign expenditures, that such expenditures pose unacceptable risks of political corruption—do not really have anything to do with the substance of that case. They are better understood as complaints about a different, far more important case: Buckley v. Valeo, decided by the Burger Court in 1976.

If you want to blame anything for Elon Musk’s ability to spend a flabbergasting $250,000,000 in support of Donald Trump, blame Buckley.

So let me try to set the record straight—about Citizens United, Buckley, corruption, and corporate personhood.

Really quickly, what was Citizens United?

Last week on the FLAGRANT podcast, Bernie brought up Citizens United, blaming it for Elon Musk’s big contributions to Donald Trump. The host Andrew Schultz asked a nice follow-up question.

Can you really quickly just tell the audience exactly what it is? ‘Cause I feel like we hear these words like Citizens United, and a lot of people just kind of pretend that we know what it is.

This should’ve been a lay-up. Sanders has been railing against Citizens United for over a decade. He is probably the single most famous and tireless opponent of the case, which he considers so disastrous that he’s even proposed—officially, in Congress—to overturn it by amending the Constitution.

Here’s what Sanders said.

Wealthy individuals, in a case called Citizens United (I don’t remember all the details) basically said, “look.” We had at that point—Citizens United I think is 15, 20 years—that decision from the Supreme Court, Supreme Court decision. So people go into the court and say, “Look, I have a First Amendment right to tell the people of America how I feel about an issue, or a candidate. I don’t like Andrew, and I want to spend $20 million on television ads telling people what a jerk he is.” …

And the Supreme Court says “No.” There’s campaign finance law, which limits the amount of money you can spend on a campaign. …

That’s what Citizens United did. The Supreme Court ruled that advertising is freedom of speech, and you can’t limit my speech. So if I want to spend $100 million on TV ads, I have the right to do it. They said, “You’re right.”

“I don’t remember all the details”—indeed. But that’s hardly the worst problem with Sanders’ synopsis.

Let me say this as clearly as I can. Citizens United didn’t establish that advertising is speech. The Supreme Court has ruled in the past that “campaign expenditures,” such as political advertisements, are “political expression,” but they decided that in Buckley, not in Citizens United. You could overturn Citizens United tomorrow, and next week Elon could still spend another $100,000,000 to get the word out about his favorite candidates.

The real upshot of Citizens United is, basically, that corporations also have First Amendment rights to engage in political speech.

At first, this may sound outrageous. “Corporations are people” has the same sort of ring as “2 + 2 = 5” or “Arbeit macht frei”—a blatant lie coming from those in power, which we are expected to accept as if it weren’t obviously incoherent.

But corporate personhood isn’t obviously incoherent. It’s often a good idea to say that, for legal purposes, a corporation, nonprofit, or labor union can have rights and responsibilities over and above those of their members. For example, there’s nothing silly about saying that my employer owes me money on payday, or that BP owed compensation after they caused the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Nor is it obviously outrageous to say that the AFL-CIO and New York Times should enjoy some First Amendment protection from government censorship. And by the way, Citizens United does extend that protection to labor unions, not just for-profit corporations.

To be clear, I’m not saying that Citizens United was decided correctly, or that it’s good for the country to award coporations and labor unions First Amendment rights. I’m just saying that some common critiques of Citizens United are shallow, and that some prominent critics can’t seem to explain the case’s basic facts.

Speaking of which…

The basic facts behind Citizens United

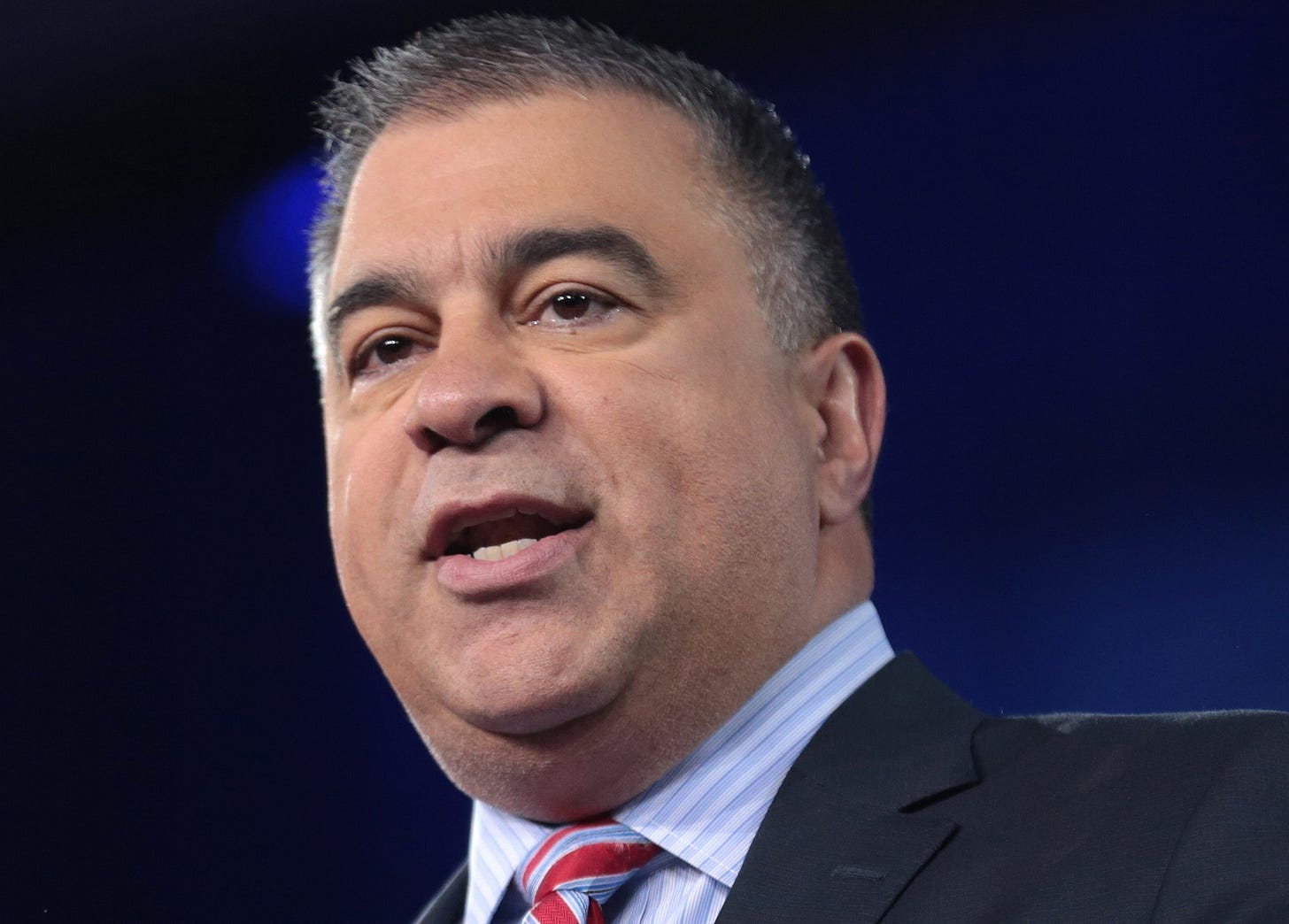

Citizens United—the appellant, not the decision—is a nonprofit founded in 1988 to advocate for conservative political causes. They’ve put out dozens of documentaries (with titles like Ronald Reagan: Rendezvous with Destiny), and they have extensive political connections. Their leader, aptly named David Bossie, took a break from being the boss to help run Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign; in 2020, he advised both Trump and Bibi Netanyahu.

Legally speaking, Citizens United is a type of 501(c)(4) known as a “social welfare organization.” Nonprofits of this sort enjoy certain legal privileges, including exemptions from income tax and from requirements to report their donors. In return, these orgs must “exclusively” use their funds for charitable, recreational, or educational purposes. (In legalese, “exclusively” turns out to mean “primarily,” which eventually became “at least 51%.”)

During the 2008 Democratic primary, Citizens United wanted to release Hillary: The Movie—a documentary that was effectively an anti-Clinton ad. But a 2002 law prevented the group from doing this; it prohibited all corporations and unions from engaging in “electioneering communications” within 30 days of the relevant election. So, Citizens United sued the FEC, and eventually the Supreme Court ruled in their favor, overturning parts of past cases.

There’s more to the story, of course. It’s probably worth knowing that SCOTUS treats laws that restrict First Amendment rights as “subject to strict scrutiny,” whch means they have to be narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling interest. And it’s definitely worth watching Stephen Colbert’s lawyer explain how a 501(c)(4) shell corporation (aka “campaign finance glory hole”) can funnel anonymous donations to a Super PAC. But here I’m just trying to cover the basics.

Back to Buckley

The deeper pathologies of American campaign finance—which allow Elon Musk to spend $250,000,000 to help Donald Trump get elected, and which allow Trump and other wealthy candidates to self-fund their bids for office—come from the case I mentioned earlier, Buckley v. Valeo.

Here are some essential facts about Buckley.

Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act in 1971 and beefed it up in 1974, thereby putting sharp limits on both campaign contributions and campaign expenditures (among other things).

Contributions are when you give money to a candidate or his campaign. The FEC Act said that an individual could give at most $1,000 to any particular candidate, and at most $25,000 in one election season.

Expenditures are when you spend money yourself in a way that helps the candidate. The FEC Act limited an individual’s expenditures to $1,000 for an individual candidate.

In Buckley, the Supreme Court struck down the limits on expenditures as unconstitutional, while allowing for restrictions on contributions.

Why the disparity? The reasoning here was that only contributions have a risk of creating corruption—specifically, quid pro quo corruption. If you just spend your own money trying to help Buckley get elected to the State Senate (say, running ads and buying airtime to argue on his behalf), he’s not going to do you any favors. But if you give Buckley cash, you can cut an illicit deal with him.

But why strike down limits on expenditures? Because, the Court says, money is speech, so the government can’t pretend that it respects the First Amendment right to free speech if it’s capping expenditures. Those expenditures are really “political expression.” As one footnote puts it:

Being free to engage in unlimited political expression subject to a ceiling on expenditures is like being free to drive an automobile as far and as often as one desires on a single tank of gasoline.

These arguments are not, in my view, especially persuasive.

First, quid pro quo corruption isn’t the only kind worth worrying about.

Second, big expenditures obviously can lead to a quid pro quo. (Does anyone think DOGE would have happened without Elon Musk’s expenditures the year prior?)

Third, I’m not convinced that spending huge sums of money should count as protected speech, particularly in a contested election where there is limited attention and airtime, so that one person’s spending can crowd out another’s.

So I think there is ample room for critiquing Buckley. But that’s not what Sanders was doing with the boys at FLAGRANT. On the contrary, he ran roughshod over Buckley’s crucial distinction between expenditures and contributions, implying that Citizens United was responsible for allowing Musk to “contribute” to Trump’s campaign. This is doubly confusing: it’s the wrong court case and the wrong type of spending.1

Morals and myths

I have to say, it’s disappointing that so many Americans aren’t taught about Buckley. It’s even worse that so many have been spreading myths and exaggerations about Citizens United.

If there’s a moral to this story, maybe it’s that you shouldn’t get your civics lessons from entertainment podcasts.

Instead, might I recommend treating yourself to Ian Shapiro’s Power and Politics? In addition to being a first-rate political theorist, Shapiro’s a JD who knows his finance, which makes him unusually well-positioned to explain how money got into our politics and why it’s doing so much damage.

Sanders is right that these are important issues. Billions of dollars, and the health of American democracy, are at stake. That’s precisely why we need to get the facts right.

To Sanders’ credit, Buckley and other cases are properly explained in a fact sheet on his website devoted to his “Democracy is for People” Amendment. (Jon Tester, a moderate populist, was also able to explain Buckley even as he harshly critiqued Citizens United.)

But in speeches and interviews, Sanders tends to mischaracterize Citizens United, though sometimes he just oversimplifies, as he does here:

Citizens United…essentially says that corporations and billionaires can…decide who will become president, senator or a governor.

Isn't the whole "is money speech?" stuff distracting? If I self-publish a book supporting candidate X, that's clearly speech / political expression. But it costs money. If there are limits on expenditures, then once I've paid to print a large enough number of copies, the government can stop me from printing more; that is, a law limiting expenditures permits the government to censor my book. Since the gov't can't stop me from printing as many cookbooks as I want, this is a content-based restriction. Clearly a violation of the First Amendment!

This is helpful. I had not heard of Buckley before now, and I suspect most other people in my position (educated but not experts in con law or campaign law, but worried about money in politics) are similar.