Halfway through last year’s The End of Race Politics, Coleman Hughes arrives at “perhaps the single most shocking graph relating to American race relations” (p. 92).

It’s hard not to be shocked. In 2001, solid majorities of Whites and Blacks told Gallup that relations between the two races were “somewhat” or even “very good.” By 2021, they were saying the opposite. Black optimism had plummeted from an astonishing 70% to a baleful 33%, as White optimism tumbled from 62% to 43%.

What went wrong?

“Neoracism” and colorblindness

We can’t pin the blame on any one politician, says Hughes. The decline began in 2013—five years after Obama’s historic election, and two years before Trump’s historic escalator ride. Nor does he think we can blame a rising tide of White racism; support for groups like the KKK had by 2013 been dropping for decades.1 Hughes instead blames a new ideology—what he calls “neoracism,” the bête noire of his first book—which spread like wildfire with the advent of smartphones and social media.

According to “neoracists,” our racial problems need racial solutions. White people should openly proclaim their privileges and “strive to be ‘less white’”—which Robin DiAngelo defines pejoratively as being “less racially oppressive.”

As for Black people, Hughes’ neoracist thinks they should be singled out for preferential treatment in hiring, school admissions, and various government programs. “The only remedy to racist discrimination,” says Ibram X. Kendi, “is antiracist discrimination.” It is certainly not enough to shun stereotypes and opt for “colorblind” systems that treat like cases alike. Wherever we find racially disparate outcomes, the system that produced them must itself be racist, and should therefore be abolished. If Black students fail standardized tests, don’t “close the gap”—ban the tests. If Black drivers get more tickets from traffic cameras, don’t serve the fines—tear down the cameras.

To Hughes, neoracism is nothing short of a moral and political disaster. Although neoracists claim to be the next coming of the Civil Rights Movement—which delivered victories for Black Americans against segregation, discrimination, and voting restrictions—the neoracists have betrayed the movement’s moral philosophy and have few political wins to show for it.

At the core of the Civil Rights Movement, Hughes argues, was a philosophy of colorblindness, which he sees as a moral aspiration: “we should treat people without regard to race, both in our public policy and in our private lives” (p. 19). Why? Because race is a shallow and “arbitrary” characteristic, not part of the essence of who we are as human beings (p. 5).

Today’s progressives, however, tend to see colorblindness as passé at best, white supremacy at worst.

When Hughes advocated colorblindness in a TED talk, the “blowback” from staffers was strong enough that TED refused to publish the video without an “extension,” in which Hughes and Jamelle Bouie were to debate whether colorblindness “perpetuates racism.”2

In The End of Race Politics, we get to hear Hughes speak his mind without someone else twisting his arm. And we’re lucky for it. The book is forceful, clear, and honest—a too-rare trio.

But that’s just to say that Hughes is worth reading. Is he right?

While Hughes does land some heavy blows against “neoracists,” I think he also underrates the costs of going colorblind.

Even during the heyday of the Civil Rights Movement, there were conflicts between more colorblind groups—like Roy Wilkins’s NAACP and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s SCLC—and the avant-garde SNNC, which embraced Black Power in 1966 and expelled its White members the following year. “Black Power” comes up in Hughes’ book only twice—in denouncements from King (pp. 60, 65) and Wilkins (p. 60). Hughes never grapples with the idea that it might be okay to be proud of one’s race, or that Black people might legitimately prefer a church, neighborhood, or college where they can enjoy some relief from being in the minority.

My objection isn’t that Hughes downplays racism. It’s that he downplays the tradeoffs we have to make when choosing how to fight against racism.

But let’s start by giving credit where it’s due.

The case for colorblindness

I found myself coming back to Hughes’ book last week, as the Washington Free Beacon published a much-discussed article on DEI at the Harvard Law Review.

Just over half of journal members [i.e. students in charge of the journal]…are admitted solely based on academic performance. The rest are chosen by a “holistic review committee” that has made the inclusion of “underrepresented groups”—defined to include race, gender identity, and sexual orientation—its “first priority,” according to resolution passed in 2021.

The law review has also incorporated race into nearly every stage of its article selection process, which as a matter of policy considers “both substantive and DEI factors.” Editors routinely kill or advance pieces based in part on the race of the author, according to eight different memos reviewed by the Free Beacon, with one editor even referring to an author’s race as a “negative” when recommending that his article be cut from consideration.

I don’t think too many Americans like the the idea of treating author’s race as a “negative.” It doesn’t seem fair. It also defeats the point of an academic journal, which is to publish good work.

This is the kind of policy Hughes calls “neoracism.”

The paradigm here is affirmative action: the preferential treatment of certain groups when making decisions about whom to hire, promote, and admit.

Such policies tend to make race “pop out.” If the Asian students at your university score, on average, 450 points higher on the SAT than their Black classmates—which used to be the actual disparity between Black and Asian students with the same chance of admission to Harvard (p. 166)—then your classmate’s race will suddenly convey a lot of information, and it will be that much harder to see them as an individual.

As you’d expect, Hughes thinks that neoracism is illiberal and unfair. But he has another objection. Neoracist policies are so un-American that they can only survive here with the aid of deception.

As Hughes argues, values like common humanity and equal treatment are deep in the DNA of American anti-racist politics, dating back to the days of abolition. Wendell Philips, head of the American Anti-Slavery Society, called for a fourteenth amendment to create “a government color-blind” (p. 47), and held that “the work of the great anti-slavery movement” would not be complete until the nation was pledged to “the principle that there shall be no recognition of race by the United States or by State law” (p. 48). In John Marshall Harlan’s legendary dissent to Plessy, the justice declared: “Our Constitution is color-blind” (p. 50)—a saying that would become the “basic creed” of Justice Thurgood Marshall, in the words of one aide (p. 51).

Do I even have to mention Dr. King? Any American who has reached the age of object permanence can tell you the most famous line of his most famous speech:

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

We also find colorblind ideas in the bill inspired by King’s movement, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which contains text in Title VII explicitly denying any intentions to effect “preferential treatment.” One sponsor in the Senate even called the bill “‘color-blind’ with respect to preferential hiring” (p. 56).

This history, summed up in Hughes’ second chapter, is perhaps a bit too neat. In early 1964, King did call for “some concrete, practical preferential program, … a crash program of special treatment” meant to help Black Americans. But soon he and his advisors changed course, emphasizing that any “Negro Bill of Rights” would have to “give greater emphasis” to the plight of “the so-called ‘poor white’.”

Color and camouflage

If America has colorblind DNA, how did “neoracist” policies flourish for so long?

One reason, in my view, is that we have a history of anti-Black racism, which seems to call for some kind of race-conscious response. Roy L. Brooks puts it well at the start of Integration or Separation?

Two persons—one white, the other black—are playing a game of poker. The game has been in progress for some 300 years. One player—the white one—has been cheating during much of this time, but now announces: “from this day forward, there will be a new game with new players and no more cheating.” Hopeful but suspicious, the black player responds, “that’s great. I’ve been waiting to hear you say that for 300 years. Let me ask you, what are you going to do with all those poker chips that you have stacked up on your side of the table all these years?” “Well,” said the white player, somewhat bewildered by the question, “they are going to stay right here, of course.” “That’s unfair!” snaps the black player. “The new white player will benefit from your past cheating. Where’s the equality in that?”

I think Hughes would agree that there’s something to this.3

But there’s another reason for neoracism’s survival: it’s often cloaked in deceptive language.

Hughes illustrates with a pair of polls taken in February 2019. In one, Pew asked 6,637 Americans about the role of race in college admissions; in the other, Gallup asked 6,502 Americans about “affirmative action.” The results: Pew found that “73 percent of respondents said that race should not be a factor in college admissions. But 61 percent of respondents to the Gallup survey said they supported affirmative action programs for racial minorities” (p. 164). The very name may be tricking people into supporting a policy they morally oppose.

More recently, affirmative action has faced opposition from the courts.4 In 2023, the Supreme Court ruled that most race-based college admissions are unconstitutional. No doubt, admissions officers will find creative ways around the law. But such efforts will require yet more obfuscation, as universities strive to achieve a diverse mix of students without leaving any evidence of how they do it.

Is all this duplicity worth it? Hughes doesn’t see much payoff. Elite universities get to boast of their diversity, but this “pretense of social concern” yields few tangible gains for the most disadvantaged Black Americans (p. 168). According to one sociologist’s estimate from 2012, only 1% of America’s Black and Hispanic eighteen-year-olds enjoy a boost from affirmative action in a given year; moreover, most Black students admitted to Havard aren’t descendants of American slaves, but are instead children of wealthy parents from overseas (pp. 167–68).

Nor are the benefits of such policies likely to last, since they are so easily clawed back by the moral-legal riptide.

Consider two short-lived COVID-era programs. In 2020, the CDC decided to prioritize vaccines for “essential workers” over the elderly, a policy that would predictably lead to more deaths for White people and for Black people. The rationale for this choice was, basically, that the elderly were less poor and less diverse. “Thankfully, public outcry over the decision led to a last-minute reversal” (p. 72). A similar fate befell President Biden’s “Restaurant Revitalization Fund.” At first, the fund gave priority to businesses run by “women, veterans, and socially and economically disadvantaged individuals” (p. 70), effectively disqualifying White men. Before long, the courts ordered the fund to rescind a portion of the $28.6 billion that had “already been promised to restaurant owners in the priority group”—a “double dose of racial discrimination” (p. 71).

In politics, sometimes you have to change hearts and minds, and sometimes you have to work with the hearts and minds you’ve got. Given the history of America’s political morality—its egalitarian roots, its North Star of equal treatment, its decades of post-Brown Supreme Court precedent—it is hard to see a clear future in a policy of giving open preference to one racial group over others.

The costs of colorblindness

What about colorblindness? Does it have a future in American politics?

Maybe. But let me lay out what I see as the main three problems.

The first is that colorblind policies tend to produce racially disparate outcomes. If Black people begin at a disadvantage, colorblindness won’t fix that. And if groups differ in demographics or culture, that by itself may lead to disparities (pp. 110–11), on top of those due to the almighty forces of random chance. How can we justly allow one racial group to be poor while others are rich?

Hughes has a response, which is that racial disparities aren’t always unjust. Some disparities are malignant—namely, those produced by “discrimination” or some other “unfair process” (p. 109). But others are benign—they “arise naturally because of cultural and demographic differences between groups” (p. 109). (I would add “or because of random chance.”) Hughes thinks we can live with benign disparities, and he warns that “invasive procedures to remove them,” such as preferential hiring, may “do more harm than good” (p. 109).

But if a fair process leads to big “benign” disparities, one race might still be left desperately poor. Does Hughes think we should tolerate this? Not at all. Like the later King, who was inspired by Bayard Rustin, Hughes favors class-based policies to aid the truly disadvantaged—whatever their race.

The result is an attractive package: treat malignant disparities as race problems to be solved with anti-discrimination laws, and treat “benign” disparities as economic problems to be solved with race-neutral redistribution and social services. (At least, do this when the “benign” disparity is so vast that one group is left in poverty. Some disparities we have to live with.)

But benign disparities lead to a second problem, which Hughes doesn’t consider. In a world of disparities, “neoracist” behavior can emerge without “neoracist” intentions.

Imagine Bob lives in a colorblind society, where racist bigotry is stigmatized, and there are few racists still around. Now suppose Bob works in the math department, which, thanks to the college’s colorblind hiring, has always hired the most qualified candidates. This process usually leads to a diverse faculty. But Bob’s department, through sheer chance, has a “benign disparity”—they’re all White. Won’t Bob worry about how this looks? Even if he knows he’s not racist, any rational observer will at least be suspicious. This gives Bob a powerful incentive to make his department more diverse, even if Bob’s values are intrinsically colorblind.

So while Hughes tends to dismiss neoracism as a grift, it can also be strategic behavior. Even if you’re not “woke” at heart, you may find yourself tempted towards woke behavior—affirmative action, “political correctness,” etc.—as a means of proving that you’re not a racist. Even racists might do it, if only to convince themselves!

Unless people stop caring about being stigmatized, “neoracism” is never going to disappear completely, and we’re never going to live in a completely colorblind world.

This isn’t a devastating objection, though—just a splash of cold water. For all that’s been said, we might still have good reasons to make the U.S. more colorblind. And in fact I agree with Hughes that we should take the case for colorblindness more seriously when it comes to hiring, publishing, college admissions, and many other matters of concern.

But what about dating? What about historically Black universities? What about churches and cultural groups? Are we supposed to stigmatize people who are proud of being Black or Asian or Latin American?

We’ve arrived at, in my view, the third and most serious problem for colorblindness, which is hiding in the blind spot of Hughes’ book.

Race vs. ethnicity

The trouble starts with “race.”

As Hughes puts it, the concept of race is like that of a month: “a social construct inspired by a natural phenomenon” (p. 4). Just as a month loosely fits the lunar cycle, our racial categories loosely track each “cluster of similar genomes” created by “the major out-of-Africa migrations” (p. 5). But now the concept of a race has a life of its own, and we categorize people into races using arbitrary rules with no basis in biology. Barack Obama, for example, is treated as Black rather than White, despite being half of each—a vestige of “the old one-drop rule” (p. 6). Such rules are not the stuff of real science, and they are not the sorts of things we should have in mind when we think about our friends and neighbors.

Thankfully, the one-drop rule has lost its legal oomph, as the U.S. Federal Government Census now invites Americans to check the box for multiple races. But Hughes still finds the boxes arbitrary. “Black, Hispanic, White, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaska Native”—this “canonical list of five categories” does not reflect deep facts about anyone’s humanity, only a “vague mix of intuitions about racial differences” (p. 6).5

Granted: if races were just an armchair attempt at biological taxonomy, the topic of race would indeed be “boring” (p. ix), and caring about race would be as arbitrary as caring about eye color.

But this is not what race actually means in our politics. As the social theorist Joe Heath has argued, much of America’s discourse about “race” is really concerned with conflicts between ethnic groups—particular communities that tend to share features like culture, language, religion, music, and history. In other countries, minority ethnic groups often belong to the majority race—think of Francophones in Quebec or the Ainu in Japan. But in America, we often use “race” as a clunky proxy for ethnicity, and we often say “Black” when we have in mind a more specific ethnic group: the descendants of Africans forcibly brought to America to work in slavery.

Even if race is arbitrary, as Hughes believes, it would be hard to say the same of ethnicity. People who share a religion or language will reasonably want to live nearby. People who share a culture may reasonably resent pressures to “assimilate” to a majority who does not value their identity.

You might expect Hughes to be down on ethnic pride. But here’s the start of Chapter 1:

For most of my life, I saw my mother as neither black nor white. Her Puerto Rican father was darker-skinned than me and her Puerto Rican mother was a light-skinned as any white American I knew. My mother emerged a perfect blend of the two: a light-brown hue that suggested neither blackness nor whiteness—at least not to my mind. … She would sometimes describe herself as “of color.” But whenever she really cared to show her identity, she would say she was Puerto Rican, and more specifically Nuyorican—a person who grew up in one of the Puerto Rican enclaves of New York City.

Nuyorican pride makes sense, Hughes thinks, since there is more to this identity than skin color and ancestry—two traits that have “nothing essential” to do with “human well-being” (p. 16). To be Nuyorican is to belong to a particular community at a particular place and time. While the community’s sense of itself has something to do with skin and origin, these aren’t its essence.

But what if being Black is—in the context of certain political conflicts—less like having green eyes and more like being Nuyorican?

That’s certainly how many opponents of colorblindness think of Black identity. I don’t mean the racists. I mean people who believe in racial equality while opposing racial integration.

Heath has some revealing examples. In Black Power, Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton declare that “integration, as traditionally conceived, would abolish the black community” (p. 55). In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates describes the feeling, conjured by his time at the majority-Black Howard University, that “we were something, that we were a tribe – on one hand, invented, and on the other, no less real” (p. 56).

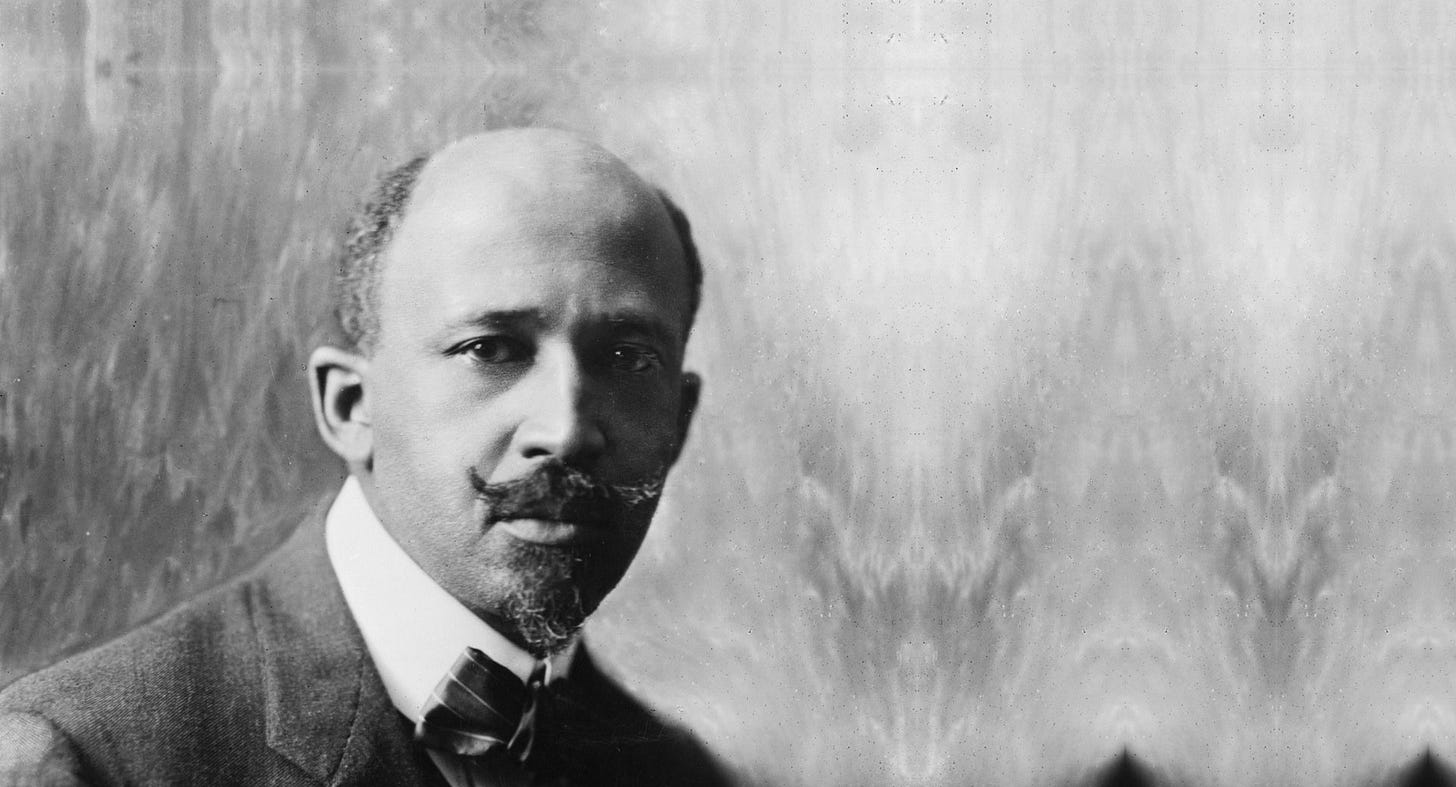

If I may give my own example, here’s W.E.B. Dubois in “The Conservation of Races.”

We are that people whose subtle sense of song has given America its only American music, its only American fairy tales, its only touch of pathos and humor amid its mad money-getting plutocracy. As such, it is our duty to conserve our physical powers, our intellectual endowments, our spiritual ideals; as a race we must strive by race organization, by race solidarity, by race unity to the realization of that broader humanity which freely recognizes differences in men, but sternly deprecates inequality in their opportunities of development.

To “conserve” the race’s assets, Dubois calls for “Negro colleges, Negro newspapers, Negro business organizations,” and so forth. This is a plea for separate but equal institutions.

Such institutions, of course, have been irrevocably stigmatized for Americans by their association with Jim Crow laws, which the Supreme Court sanctioned in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, one year before Dubois’s piece. Far from “deprecating inequality,” Jim Crow perpetuated it. But when the Supreme Court overturned Plessy in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, the result was not a revival of Dubois’ dream—it was a repudiation. “Separate but equal” was deemed impossible on the grounds that separating Blacks from Whites inherently makes Blacks feel inferior.

I wouldn’t call Dubois a “neoracist.” Dubois, like others, is just concerned that integration would erase a distinctive African-American identity.6 In a colorblind world, there would be no more distinctively Black music or art, no Black English, no Black colleges striving for Black excellence. Or rather, if any of these things were to be conserved, it will have to be a coincidence, rather than the result of conscious organization.

If you are not disturbed by the prospect of such cultural loss, you are not only colorblind but ethnicity-blind—a much more difficult attitude to sustain.

This, in my view, is the most serious cost of colorblind politics. Since American “race” relations are often ethnic conflicts, “colorblindness” means we have to be blind to ethnic ties. But that’s a big lift. Unlike mere color, ethnic identity can be a legitimate part of how we see ourselves as human beings and how we acquire self-respect.7

The result is that colorblind politics is both less desirable and less feasible than we might have hoped. Because the costs of colorblindness fall upon the ethnic groups who must assimilate, it invites political resistance from anyone who shares Coates’ and Dubois’ desire to be a “tribe”—or to put it another way, a nation—with separate but excellent institutions.

The end?

If The End of Race Politics is right about Blackness—if it is a superficial property, only weakly correlated with what decent people care about—then it shouldn’t be too hard to convert people to colorblindness. For if race is shallow, so is racism. The only intellectual pillars of racism, on Hughes’ analysis, are pseudoscience and crass self-interest. “Racial strife is what fuels the neoracist industry” (p. 177)—but once they’re out of business, we’re golden.

I’m a bit less optimistic.

Concepts like Blackness, far from skin-deep racial categories, often denote ethnic identities. So if we opt for colorblindness, we’ll be dissolving the ties that bind ethnic groups together.

But I wouldn’t say I’m against colorblindness. What’s the alternative? There may be some contexts, like Black History Month, where we want people to “see color.” But if we go full Kendi, we risk forsaking some of the country’s highest ideals—and getting struck down by SCOTUS.8

Hughes’ book, all told, isn’t “blasphemy.” I just think his defense of colorblindness might be incomplete, given the strategic appeal of “neoracism” and the legitimate value in “seeing ethnicity.”

To put it another way, I don’t expect Race Politics will literally End anytime soon. Still, Hughes has given us an important book—one that must have taken real guts.9

Hughes also says that, by 2013, there had been a steady decline in police violence against Black men. I have some doubts about this. I also wonder if the decline of race relations might have been partly a backlash to Barack Obama, particularly after “Gates-gate.”

For the jot and tittle, see Hughes’ post-mortem, plus TED and Adam Grant’s reply. The vibes have undoubtedly shifted since then, especially with Trump cracking down on DEI.

Even Hughes’ mentor John McWhorter, author of Woke Racism, agrees there’s something to be said for race-conscious policies. He once gave this analogy:

I think that racial preferences should be applied like chemotherapy: they do something well, but you don’t do it forever because it creates too much other damage.

Not to mention Trump’s executive orders.

This list is not quite accurate anymore. According to the U.S. Census, the U.S. Office of Budget and Management “requires five minimum categories” for census surveys; these are “White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.” Rather than a race, “Hispanic” is the sole “ethnicity.”

Integration, in other words, would mean submerging into “White culture.” On what “White” means for Americans, I really do recommend Heath’s “Two Dilemmas for American Race Relations,” which provides a refreshingly international perspective. (Heath is Canadian.) And for a counterpoint, see Richard Ford’s Racial Culture: A Critique, which draws out some problems with legally recognizing cultural traits of ethnic groups. (Or see Sowell.)

Ethnic solidarity may also promote self-esteem. As Hughes notes, when Kenneth and Mamie Clark studied Black students during Jim Crow, the Clarks found that “kids who attended segregated southern schools had higher self-esteem than the northern kids who went to integrated schools” (p. 54).

Though not everyone likes Black History Month, as 60 Minutes once learned from Morgan Freeman.

I’ve been tinkering with this piece since Feb. 2024, and many people have helped along the way. Thanks to Abbey Burke, Dan Wodak, Matthew Hammerton, Dustin Axe, Julius Krein, Joe Heath, Tyler Cowen, and Carla Merino-Rajme.

Refreshingly careful piece. You make all the right distinctions, like ethnicity being the real thing behind “racial relations.” On integration, speaking from a majority mixed-race country (Brazil) where different races are under the same broad ethnicity, what we do here is to associate ethnicity to location. There’s no risk of black culture from Bahia disappearing into the majority culture because, well, it’s in Bahia. Same thing for white gaucho culture in the South. While we know one is more black and the other more white, we rarely think it’s all black or all white (or all indigenous, or all caipira). We’re used to thinking there will be racial variation within each ethnic group. As for our famous music, we know that Samba, for instance, is not all black and we have great white sambistas in our history. Still, Samba is indeed thought of as blacker than Bossa Nova. What wokeness brought us, to our detriment, was the emphasis on this dichotomy, which is very American and not very Brazilian. We are now rediscovering mestizos, the majority of the country, thanks to work by intellectuals like Antonio Risério.

Really nice piece.

On the idea that colorblindness dissolves ties that bind ethnic groups together, I think the point can be put even more strongly. In a thoroughly colorblind society, there wouldn’t even be ethnic distinctions. That is, ethnic distinctions only persist because of disparities in mate choice. If Nuyoricans were no more likely to couple with other Nuyoricans than with anybody else, then it doesn’t take too many generations before you don’t really have Nuyoricans anymore.

This is sort of what’s already happened with lots of “white” ethnic groups in the United States. My maternal grandmother immigrated from Poland before the holocaust (the rest of her family didn’t get out), and when she got to the United States, she was in Jewish social circles, where she met my Jewish maternal grandfather. Jewish ethnic identity persisted into the next generation (my mother), but more weakly, so it wasn’t surprising that my mother married a man (my father) with two Italian parents. Parallel story on his side. For me, while I have both Jewish and Italian ancestry, neither played a role in my life anything like the one they did for my grandparents, and so no surprise that when I got married, the woman I married was neither Jewish nor Italian, and I don’t think my children will have any sense of a distinctive ethnic identity the way all eight of their great-grandparents almost certainly did.