Never forget

In the War on Terror, a traumatized nation made tragic mistakes. Are we already forgetting our history?

Most American college students were born in the mid-2000s, well after the 9/11 terror attacks, and towards the tail end of George W. Bush’s second term. Some of them faintly remember Barack Obama’s first election. None can recall the 2003 invasion of Iraq or the heady beginnings of Bush’s War on Terror.

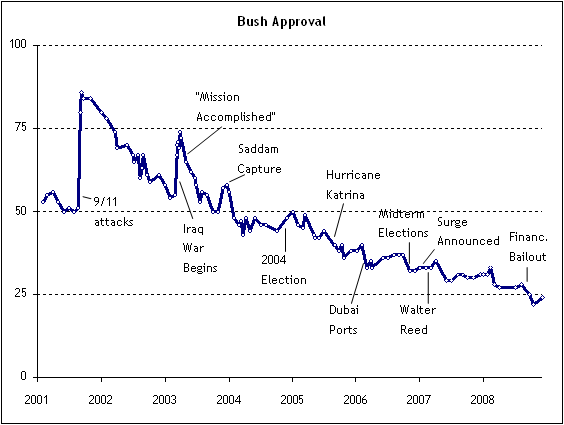

After 9/11, Bush’s approval ratings skyrocketed to an astonishing 86%—more than Trump’s and Biden’s approval ratings combined.1 The atmosphere was one of national consensus and omnipresent patriotism. It was an era of flag pins, freedom fries, and evangelicalism. It was also the golden age of patriotic country songs, most famously “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning),” with its syrupy everyman chorus:

I’m just a singer of simple songs

I’m not a real political man

I watch CNN, but I’m not sure I can tell you

The diff’rence in Iraq and IranBut I know Jesus, and I talk to God

And I remember this from when I was young

Faith, hope and love are some good things He gave us

And the greatest is love

(“Fake News CNN” had yet to be coined.)

In this emotional time, the Bush Administration had to decide on a response to the 9/11 attacks, which had killed over 2,900 people and injured thousands more. Some analysts recommended a focused strike on Al Qaeda, the group behind the attacks, which had its roots in “the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan in the 1980s.” But Bush and VP Dick Cheney rejected these narrowly tailored plans. They opted for regime change in Afghanistan. Soon they had their sights on Iraq, as well. As early as 9/14/2001, Bush had reportedly told British PM Tony Blair that he wanted to “hit” Iraq, despite a lack of evidence connecting Hussein to 9/11. Days later he would say something similar to the (baffled) Saudis. In 2003, Bush’s wish became reality. The War on Terror was on.

Bush’s wars were an extreme reaction, to be sure. But the Bush Administration was enjoying extreme levels of public support. Even Americans who had misgivings felt it unwise to speak up. In March 2003, barely a week before the invasion of Iraq, the Dixie Chicks’ lead singer told an audience in London:

Just so you know, we’re on the good side with y’all. We do not want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.

This led to a swift, humiliating cancellation. (Though we didn’t used to call it that.) Dozens of radio stations blacklisted the Dixie Chicks. DJs got suspended for playing their music. Lipton cancelled a promo contract. Their own tour bus driver quit in protest. So many death threats poured in that the band resorted to using metal detectors at their shows.

You can imagine what this did to the broader political environment. As Dave Chappelle put it in his 2004 special For What It’s Worth,

I almost protested the war in the beginning—almost. Until I saw what happened to them Dixie Chicks. I said, “Fuck. That.” If they’ll do that to three white women, they’ll tear my black ass to pieces.

(“For What It’s Worth” is also the name of an iconic protest song—for whatever that’s worth.)

But like Bush’s approval ratings, the national mood would soon sour. Bush was harshly criticized for his response to Hurricane Katrina; for his nomination of Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court; for his oratory bumbling (e.g. “the internets”); and above all for the quagmire in the Middle East.

People started resenting the sanctimonious culture that had insulated Bush from criticism. This was the era of American Idiot, Rock Against Bush, Jon Stewart’s Daily Show, The Colbert Report, and “Freedom Isn’t Free.”

Eventually much of the country came to believe that the Iraq War had been launched on the basis of bad information—if not outright lies. Saddam Hussein had not been part of the 9/11 attacks. Iraq had not been in possession of weapons of mass destruction. Roughly 100,000-200,000 civilians were killed in the Iraq War, along with 4,500 US troops. The United States spent roughly $2,000,000,000,000 (yes, two trillion dollars) fighting that war along with the ensuing war against ISIS. The country also debased itself by waterboarding, sexually humiliating, and otherwise torturing both soldiers and civilians in secret prisons.

The result was a profound loss of faith in the Republican establishment—and in the Democrats who had gone along with them. One such Democrat was Hillary Clinton, who voted to give Bush the authority to go to war. She described this as “probably the hardest decision I’ve ever had to make,” but nevertheless cast her vote “with conviction.”

This abysmal, bipartisan failure helped set the stage for the rise of Donald J. Trump, one of the few prominent Republicans willing to denounce the war in strong terms. First Trump wiped the floor with Bush’s brother, Jeb, in the Republican primary. Then he stunned the world by defeating Clinton in the general.

Obviously, the War in Iraq was a big, fat mistake.

We should have never been in Iraq. We have destabilized the Middle East.

I want to tell you: they lied. They said there were weapons of mass destruction. There were none, and they knew there were none. There were no weapons of mass destruction.

The World Trade Center came down during your brother’s reign. Remember that. That’s not keeping us safe.

In August 2021, Trump’s successor Joe Biden would finally withdraw troops from Afghanistan. Within days, the Taliban took back control of the country, a fiasco that likely emboldened Vladimir Putin to invade Ukraine in February 2022. After the fall of Kabul, Biden’s approval ratings never recovered—which was a major factor, possibly a decisive factor, in Trump’s victory over Biden’s VP Kamala Harris in 2024.

So here we are in 2025.

Although we are no longer under threat from Al Qaeda and Osama Bin-Laden, the War on Terror is now widely seen as a historic catastrophe—a tragic injustice, costing hundreds of thousands of lives and trillions of dollars, that has profoundly shaped American politics well into the 21st century.

Why would anyone want another war on terror?

That’s the question that I can’t help but ask as I listen to conversations from major figures in the White House, which are taking place in the wake of Charlie Kirk’s assassination.

Last September 10, Kirk was assassinated during an event at Utah Valley University. The overwhelming response among prominent Democrats was to denounce the shooting and call for unity—Schumer, Jeffries, Obama, Harris, and so on. But some leaders, like Ilhan Omar, took the opportunity to denounce Kirk’s views. Heather Cox Richardson made false claims about the political allegiance of the shooter in her 9/13 newletter, saying that he “appears to have embraced the far right, disliking Kirk for being insufficiently radical.” Many online figures celebrated the killing, or at least proudly refused to condemn it.

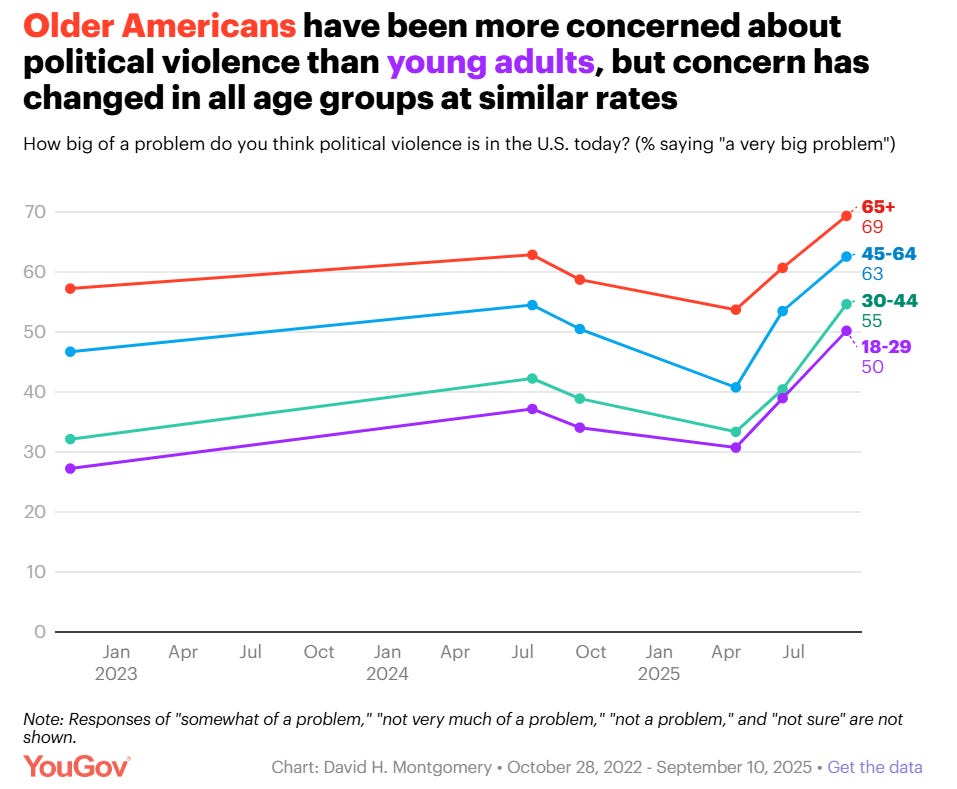

Any killing is a tragedy, but our political problems go beyond any single killing. According to polling from YouGov, the taboo on political violence—though still significant—is considerably weaker among younger Americans.

It is against this background that J.D. Vance and Stephen Miller are calling for a prosecution of “leftwing organizations” that commit or support terrorism. It is not yet clear what this campaign will involve. Will it be narrowly focused on groups that perpetrate or at least plan violent acts? Or will it become a crackdown on entire networks of progressive groups, even if they are connected only tenuously to a handful of violent actors?

During a special episode of the Charlie Kirk Show, Vance assured the audience that the campaign will respect free speech.

You have the crazies on the far left who are saying, “Oh, Stephen Miller and J.D. Vance, they’re going to go after constitutionally protected speech.” No, no. We’re going to go after the NGO network that foments, facilitates, and engages in violence. That’s not okay. Violence is not okay in our system. And we want to make it less likely that that happens.

But I have to admit that I felt uneasy hearing Miller, the Deputy White House Chief of Staff, explain his plans.

The last message that Charlie sent me was…that we need to have an organized strategy to go after the leftwing organizations that are promoting violence in this country. And I will write those words onto my heart, and I will carry them out.

If people ask me, you know, what emotions I’m feeling right now…. There’s incredible sadness, but there’s incredible anger. And the thing about anger is that unfocused anger or blind rage is not a productive emotion. Right? But focused anger, righteous anger directed for a just cause is one of the most important agents of change in human history. And we are going to channel all of the anger that we have over the organized campaign that led to this assassination to uproot and dismantle these terrorist networks. …

The organized doxing campaigns, the organized riots, the organized street violence, the organized campaigns of dehumanization, vilification, posting people’s addresses, combining that with messaging that’s designed to trigger, incite violence, and the actual organized cells that carry out and facilitate the violence—it is a vast domestic terror movement. With God as my witness, we are going to use every resource we have at the Department of Justice, Homeland Security, and throughout this government to identify, disrupt, dismantle, and destroy these networks and make America safe again for the American people. It will happen, and we will do it in Charlie’s name.

I remember hearing American leaders talk about incredible sadness and righteous anger. I remember hearing American leaders dismiss their critics as unpatriotic crazies. I remember promises that the War on Terror would be a defense of freedom, that it would be over in a flash, that we would be greeted as liberators.

I also remember the feeling of betrayal as I realized—as did so many other Americans—that the War on Terror was out of control. That it was a “big, fat mistake,” enabled by the surge of emotions that the country felt after a shocking act of political violence.

The problem of terrorism is, of course, a grave one. But as Tyler Cowen has powerfully argued, Charlie Kirk was killed by a single person, not by an organized network of leftwing NGOs. To use this crime as a pretext for an indiscriminate crackdown would be a dangerous escalation—one that would pave the way for future crackdowns by future governments.

To be clear, I’m not saying Miller and Vance have already launched a self-conscious, domestic rerun of the War on Terror.2 So far, to my knowledge, they have just been talking and planning, and we don’t know the details of their plans. I don’t want to exaggerate here.

But at risk of ending up like the Dixie Chicks, I want to speak out now, before the die is cast. Those of us who remember the War on Terror have an obligation to younger generations—and to the future—to pass on the painful lessons that we learned. When you can accuse your enemy of a crime as incendiary as terrorism, it’s all too easy to dehumanize them. When you’re feeling righteous anger, it’s all too easy for justice to devolve into revenge. When you’re on a crusade, it’s all too easy to lump all non-crusaders into a singular enemy.

“You’re either with us or against us” was a crucial plank of the Bush Doctrine, as analyzed by Ian Shapiro in Containment.

We saw what this kind of Manichean thinking did to American foreign policy. As the saying goes: “Don’t try this at home.”

Biden’s approval rating was 40% in January 2025, his last month as president. Trump’s approval rating has been below 46% since June 23 of this year.

Let me also concede that a campaign against leftwing NGOs in the US wouldn’t be as logistically fraught as trying to build a democracy in a fractious, faraway country like Iraq, where Shias, Sunnis, and Kurds were vying for power. (The rise of Shia militias in particular caught the US by surprise.)

In addition, I want to point out that there have been some potent messages of hope, including a moving speech by Erika Kirk at her husband’s memorial:

My husband Charlie, he wanted to save young men, just like the one who took his life. That young man, that young man. On the cross, our savior said, “Father, forgive them for they not know what they do.” That man, that young man—I forgive him.

I forgive him because it was what Christ did, and is what Charlie would do. The answer to hate is not hate. The answer, we know from the Gospel, is love and always love. Love for our enemies, and love for those who persecute us.

The next speech, by Donald Trump, struck a different tone. (“I hate my opponent, and I don’t want the best for them.”)

Just to clarify, the removal of forces from Afghanistan was orchestrated by the Doha Accord, negotiated and signed by the Trump Administration on 2/29/20. https://www.factcheck.org/2021/08/timeline-of-u-s-withdrawal-from-afghanistan/

It’s an odd twist of fate that the Afghan War was the more defensible of the two invasions, yet it was a complete failure, but the Iraq war, though now universally regarded as a mistake by both sides in America, ultimately succeeded in producing a stable, less authoritarian Iraq. That alone does not retroactively justify it, especially since it was launched on the basis of a lie and created ISIS in between, but it does go to show the strange and arbitrary way we evaluate wars like these. Had Trump not won in 2016 I guarantee you Republicans would still be defending the Iraq war to this day, now they all pretend they always opposed it.