Inequality isn’t the problem

Spicy Philosophical Theses (1/10)

Recently, Tyler Cowen remarked that academic philosophers have, as of late, been “losing rather dramatically in the fight for intellectual influence.” I strongly disagree. This statement is cruel and blatantly unfair to academic philosophers, whose discipline never had much influence to begin with.

…but that’s all about to change.

In a desperate ploy for attention special treat for my subscribers, I’m going to publish a series of 10 posts about ~spicy~ philosophical theses that I see as underrated in our wider intellectual culture. These 10 theses are not presented as indubitable truths. In fact, I dubit that even half of them are true. But they’re all worth a ponder.

Let me begin by cutting my subscriber count in half with:

Income inequality is not inherently bad

I know what it sounds like—but note the “inherently.”

When people decry income inequality, what are they decrying? Consider this passage from Bernie Sanders, in a 2021 piece with a very 2021 title: “The rich-poor gap in America is obscene. Let’s fix it - here’s how.”

The United States cannot prosper and remain a vigorous democracy when so few have so much and so many have so little.

Today, half of our people are living paycheck to paycheck, 500,000 of the very poorest among us are homeless, millions are worried about evictions, 92 million are uninsured or underinsured, and families all across the country are worried about how they are going to feed their kids. Today, an entire generation of young people carry an outrageous level of student debt and face the reality that their standard of living will be lower than their parents’. And, most obscenely, low-income Americans now have a life expectancy that is about 15 years lower than the wealthy. Poverty in America has become a death sentence.

Meanwhile, the people on top have never had it so good.

And from there, he goes on to cite various stats about the wealth of the 1%, name-checking Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk in particular.

Clearly, Sanders is worried about inequality itself: it’s “obscene,” he thinks, for some to have so much while others have so little. But if you look closely, you’ll see that nothing else in the passage supports the idea that inequality is inherently bad.

Sanders begins by asserting that income inequality has bad effects: it undermines prosperity and democracy. This is, of course, a legitimate problem worth pondering for any prosperity-loving democrat. But it doesn’t show that inequality is inherently bad. Something can have bad effects while being inherently neutral or even inherently good! If each of the 50 states spoke only its own language, that would make it harder for the country as a whole to communicate, undermining the country’s prosperity and democracy. That’s a bad effect. But that hardly shows that linguistic diversity is inherently bad!

Next, Sanders lays out various respects in which people are badly off. Poor Americans are in debt; they’re getting evicted; they have lower life expectancies and standards of living; they’re living “paycheck to paycheck.”1

This is inherently bad. But notice that the problem here isn’t inequality as such. The problem is the suffering. Rather than wanting the poor and rich to be equally well off, we should just want the poor to be better off than they are now.

What’s the difference? Well, if the problem were merely about rich-poor inequality, then we’d have two equally good ways to fix it. We could either (1) lift up the worst-off, or (2) kneecap the best-off. For example, if some tasteless poison seeps into the water supplies of the richest neighborhoods, we might see the life expectancies of the best-off people drop by 15 years, so that the obscene rich-poor gap in longevity disappears. This “leveling down” would achieve equality, but it wouldn’t in any way alleviate anybody’s suffering. Leveling down the position of the best-off achieves the desired distribution without helping those worst-off.2

If you think leveling down is purely bad, you’re not an egalitarian, after all. By which I mean: even if you think an equal distribution has extremely good effects, you don’t think it’s inherently good.

So what do the egalitarians have to say for themselves? The “leveling down objection” is a classic, so as you’d expect, there are some familiar replies.

The all-time classic reply is that inequality, though bad, is just one kind of badness among many. When you kneecap the best-off, you are removing one evil (inequality), but you’re also introducing another, weighter evil (the kneecapping). Larry Temkin explains:

I, for one, believe that inequality is bad. But do I really think that there is some respect in which a world where only some are blind is worse than one where all are? Yes. Does this mean I think it would be better if we blinded everybody? No. Equality is not all that matters. (Inequality, p. 282)

Making everyone equally blind, on Temkin’s view, is still overall worse than having some people be sighted while others are blind. The all-blind world is better in one way by virtue of being more equal, but the badness of losing sight outweighs the extra goodness we get from leveling down.

But this reply has two problems.

First, the egalitarians still have to admit there is something good about leveling down, which can be difficult to believe. Removing some people’s eyes—or more generally, worsening the position of the best-off without in any way improving the position of anybody else—seems like a pure loss, not a tradeoff. Derek Parfit puts it well (discussing views of egalitarians such as Temkin):

On their view, it would be in one way better if we removed the eyes of the sighted, not to give them to the blind, but simply to make the sighted blind. That would be in one way better even if it was in no way better for the blind. This we may find impossible to believe. (p. 17)

🚨WARNING🚨

The following objection contains references to formal ethics. Reader discretion is advised.

The second problem, discovered by Johan Gustafsson, is that Temkin’s reply risks making inequality negligible. Even granting that there’s something bad about inequality, if leveling down always makes things worse overall, this puts a shockingly low ceiling on how much inequality can matter.

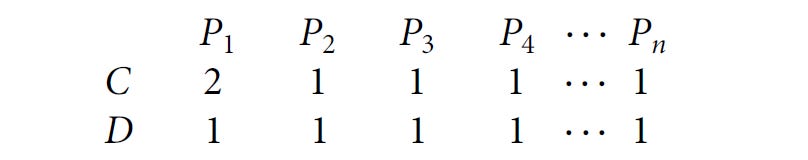

Gustafsson’s example is beautifully simple. Imagine we have one unequal outcome C, where the first person (P1) is twice as well off as everybody else, and we’re considering leveling down to outcome D, where everybody’s equal:

Here we’ve got a total of n people—where n can be as big as you want.

To add a splash of detail: imagine that C is a world of a trillion people where lucky P1 gets to live two happy centuries and everybody else lives for one happy century, and D is an alternative world where everybody lives for one happy century. The only difference is whether P1 gets the extra 100 years of happiness.

Now here’s the problem. Temkin wants to say that C is overall better than D (leveling down is bad!)—but notice that C is vastly worse in terms of inequality, and only slightly better otherwise. The only thing in favor of C over D is that extra point for P1—and yet, that measly extra point is able to outweigh an ungodly amount of inequality! Conclusion: inequality barely matters.

The key to this objection is that Temkin measures inequality in an additive way. To find how much inequality there is, you look for every difference in well-being between people, and simply add those differences up. Since C features 999,999,999,999 differences of size 1, that means the inequality is equal to 999,999,999,999. By comparison, D features no differences, so the inequality is equal to 0. That is a gigantic difference!3 And yet, this absurdly large amount of inequality gets outweighed by the puny single benefit to P1.

You could try to get around Gustafsson’s problem by adverting to a fiddly measure of inequality, but these have their own, fiddly problems, one of which I’ll mention in a footnote for the morbidly curious.4

Requiem for Equality

So is egalitarianism just a sham? A myth? A confusion?

I wouldn’t go that far! There are still a few things in the ballpark of “inequality bad” that we can say, beyond the familiar fact that inequality might have various undesirable effects on national bonhomie and political stability.

First, we might think that an unequal distribution of goods tends to make things worse because of diminishing marginal contributions to well-being. For example, having $100k is vastly better for someone’s well-being than having $0, but $1mm doesn’t make you that much better off than $900k. Thus a redistribution of $100k from a millionaire to someone absolutely broke might, other things being equal, be good for total happiness.

(Obviously, other things aren’t always equal. People won’t bother making so much money in the first place if they expect to be expropriated; sometimes it’s good to have money in the hands of people who want to invest rather than spend; etc.)

Second, we might believe that well-being itself has diminishing marginal ethical value. If you’re going to give out an extra point of well-being, better to give it to the worst-off person than the best! This view is called “prioritarianism,” and it’s basically an alternative to egalitarianism that avoids the leveling down objection. (See why?)

Third, we might be egaliatarians only when it comes to certain special goods. I have in mind what some economists call positional goods, where what matters isn’t having more, but having more than other people.5 For example, chocolate bars are not positional goods. If you have two bars of chocolate, that’s not going to destroy any of the value I get from my single bar of chocolate. But voting rights are positional goods. If my colleagues each get an extra vote in the upcoming departmental meeting, that does destroy some of the value I get from my single vote, because I end up having less influence.

(By the way, lots of goods are a mixture of both positional and nonpositional: it’s good to have more floorspace; still, most people would rather not have the smallest mansion on the block.)

With positional goods, there’s clearly something bad about an unequal distribution. The mere fact that someone has more means others have less. You can’t be at the front of the line unless everyone else gets moved back; I can’t rise in social status without someone else falling. But is inequality the problem here? To me, it seems more accurate to say that the problem is that some people lack the relevant good. Some people are suffering at the back of the line, or the bottom of the totem pole. It just so happens that when someone lacks a positional good that creates an inequality.

More importantly, if positional goods are the only type for which inequality is problematic, that is still a devastating blow to egalitarianism. Bernie ain’t gonna like it. There will be nothing obscene, on this view, about inequalities in leisure time, lifespan, gustatory delights—or, more generally, quality of life. There is nothing wrong with these disparities in themselves, and nothing admirable per se about collapsing them. The only real problem is the poverty, the deprivation.6

Finally, there is one kind of equality that I think everybody in their right minds should be in favor of: equality before the law. People who are equally culpable of similar crimes, for example, should be treated similarly by the police and the courts. There shouldn’t be arbitrary privileges based on race, sex, gender, social status, or even popularity on Substack.

I hope that’s a good first spicy thesis for you. Clearly, there is something to the ideal of equality, but it’s surprisingly hard to see why unequal distributions of goodies should be regrettable purely as such.

What other spicy philosophical topics would you like to read about?

Leave your suggestions below!

By the way, “paycheck to paycheck” is something of a fudge phrase. Besides being vague, it’s consistent with people having arbitrarily high incomes! (Big spenders live “paycheck to paycheck,” too.) Better to just talk about people’s savings and incomes directly, I say.

For a nice philosophical intro to the “leveling down objection” to egalitarianism, see Derek Parfit’s “Equality or Priority?”

Winston Churchill also referenced leveling down in a speech from 1949:

The choice is between two ways of life; between individual liberty and State domination; between concentration of ownership in the hands of the State and the extension of ownership over the widest number of individuals; between the dead hand of monopoly and the stimulus of competition… between a policy of leveling down and a policy of opportunity for all to rise upwards from a basic standard.

27 years later, Margaret Thatcher referenced it in a speech about the Labour Party.

Socialists say “equality.” What they mean is “levelling down.”

And 28 years after that, Prime Minister Tony Blair said this in a speech about his Labour Party’s goals for reform:

our approach to public services must never be about levelling down but levelling up.

Indeed, we can make the difference as big as we want by cranking up the size of n; the amount of inequality in C will be equal to n - 1. And yet this arbitrarily large amount of inequality will still fail to outweigh the measly extra benefit to P1. Inequality is, in this sense, infinitely worthless compared to actual well-being.

For example, you could measure the badness of inequality in a well-being distribution using the Gini coefficient, which equals the sum of well-being differences divided by: [the square of the population size times the average well-being level]. The convenient thing about the Gini coefficient is that it maxes out at 1, so you can’t get arbitrarily large amounts of inequality by cranking up the population size. But I still don’t recommend using the Gini coefficient to measure the badness of inequality. For one thing, this makes the badness of inequality insensitive to scaling—if you double everybody’s holdings, the Gini coefficient remains exactly the same. That means you can increase the rich-poor gap as much as you want in absolute terms without even slightly increasing the badness of inequality!

The term “positional good” has been given various definitions over the years. I’m going to go with my favorite, which was introduced by the economist Robert Frank.

In Why Not Capitalism? Jason Brennan has a punchy chapter on “Anti-Social Egalitarians” where he makes this point. As he puts it, egalitarians “misdiagnose” the problem: what matters isn’t that the poor are worse off than the rich; what matters is that they’re badly off.

It’s interesting to me that you didn’t specifically consider wealth inequality. That is, after all, the paradigmatic kind of inequality that is decried by the likes of Bernie Sanders.

One of the most common arguments against wealth inequality that I have seen is that massive amounts of wealth give rise to a type of power that is bad for the holder (because they risk becoming surrounded by yes-men) and bad for society (because those with money can use the power that results from huge amounts of cash to distort political or economic systems for personal benefits such as rent-seeking and the promotion of absurd ideologies). Money is power, and too much power in the hands of one person can be bad.

I feel like you could have started this series with an even spicier take; this one is disappointingly reasonable, I hope you escalate to "killing dolphins is good, actually" and "we should warm the planet more." But in seriousness, the psych research on socioeconomic status + health suggests that _perceived_ social status matters more than _objective_ social status; if you ask people to visualize their position on a ladder relative to others, their choice will be a better predictor of outcomes like depression, longevity, cardiometabolic functioning, and inflammation than their actual income. Which suggest that we humans are very attuned to dominance hierarchies. So I would argue that inequality is bad across the board because it creates social stress.