The day after Charlie Kirk’s (still horrifying) assassination, Ezra Klein published a piece called “Charlie Kirk was Practicing Politics the Right Way.” As you’d expect, Kirk’s critics didn’t like it. Some said his views don’t merit lionizing. Others said that he wasn’t debating in good faith—that he was dunking on college kids for content, not modeling Socratic dialogue for the good of the demos.

If you ask me, the critics have a point: Klein doesn’t really seem to think of Kirk as a role model for how to do politics, all things considered. He just thinks Kirk was right to talk to people who disagree with him.

But this critique isn’t very remarkable. As long as there have been funerals, people have erred on the side of praising the deceased. There’s a reason “eulogy” is a word and “dyslogy” isn’t.1

So let’s move on to a newer, deeper brouhaha.

I. Shame

Since the Kirk piece, Klein has been trying out a critique of the current American left: that it’s so enamored with shaming, it’s given up on talking. Rather than reaching out to win converts, the left (says Klein) is pushing people away for being problematic, as in the classic “not my job to educate you” comic.

This critique just barely shows up in Klein’s first article. It gets developed more in Klein’s preface to “We Are Going to Have to Live Here With One Another,” and a later conversation with Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Klein’s critique is (by his own admission) still a vague WIP, but the sentiment is something I’ve heard from many people, including previous generations of left-wing activists.

What was the response?

II. Táíwò

In the Boston Review, Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò raises a bunch of objections.2 The big one: Klein is too down on shame.

[Klein] contends that living with one another on the basis of “social shame and cultural pressure” cannot work and would not be worthwhile if it did: a nation where such things flourished would not be “a free country.”

What could Klein possibly mean by this?

It’s a rhetorical question. Táíwò interprets Klein as categorically condemning shame and cultural pressure as intolerable threats to freedom.

In contrast, Táíwò sees shame as a “key aspect” of how we live together. In particular, shame is part of the “moral etiquette” known as PC or wokeness, whose norms “set basic ground rules for social life—at least, in politically mixed company.” These ground rules are the basis of “civility.” They are the “bare minimum for us to exist peacefully as profoundly different people who nevertheless share the same time and place.”

Now, I doubt that “wokeness” is the “bare minimum” for a diverse civil society. (Is Singapore woke? Texas?)3

But I take the point. We need some code of civility for society to function, as Táíwò movingly illustrates with stories from his childhood. Any society has to rest on a foundation of shared mores or norms—what the legal sociologist Mark Osiel calls a “common morality,” and what Montesquieu called “The Spirit of the Laws.” This spirit runs on shame. It is the threat of shame (or “stigma”) that compels people to follow the informal norms (e.g. against racial slurs) even in the absence of legal penalties. Shame is essential, and we can’t get along without it.

Where does Klein deny any of this? Táíwò quotes two suggestive snippets. But if you look at them in context, you see Klein making a different point.

We are going to have to live here with one another. There will be no fever that breaks, no permanent victory that routs or quiets those who disagree with us. I have watched many on both sides entertain the illusion that there would be, either through the power of social shame and cultural pressure or the force the state could bring to bear on those it seeks to silence. It won’t work. It can’t work. It would not be better if it did. That would not be a free country.

Klein isn’t rejecting shame and pressure. He’s rejecting the “illusion” that we can use them to permanently vanquish our political opponents.4 That’s an infeasible end, and it can only be pursued by repugnant means—intrusive monitoring, suffocating opprobrium, government oppression, and all without end.

The real question isn’t whether shame has a place, but what the proper place of shame should be. Here I’ll offer two principles.

First, shame works best when you’re enforcing a norm that’s already broadly accepted within the relevant community (if only in its conscience). Shame doesn’t work so well when half of the community is robustly committed to the opposite norm. Trying to shame half of the country—over 100 million people!—out of their deeply held values is like trying to put out a forest fire by blowing on it really hard.

put it perfectly:My second principle is self-explanatory: don’t count on shame working where it’s had a track record of failure.

What’s Táíwò’s view of all this? He concedes that shame has a risk of being misapplied (“injustice, inaccuracy, and overreach”); that it can have “corrosive” side-effects; and that it can be implemented poorly (as in the “exuberant overreach” of 2020 and “blinkered, toothless” PC culture of the 1990s). But are there any limits, in principle, to what shame can do if implemented well? This is Klein’s key question, but I didn’t see Táíwò pondering it. (At least not in this article.)

So while I agree with Táíwò about the need for shame, I don’t agree with his take on Klein’s point. The point isn’t “shame is gross and no one should ever do it.” The point is “shame has limits, so don’t expect it to make persuasion obsolete.”

III. Coates

Now for Coates vs. Klein.

For what it’s worth, I thought this was a good conversation. I’m sorry to disappoint any readers out there waiting for the Air Muñoz dunk. (Which, if I’m being honest, is not a thing.) But I genuinely enjoyed watching Klein and Coates sharpen their views as they asked each other questions, including such classics as “What do you mean?” (Coates), and “Like, really?” (Klein).

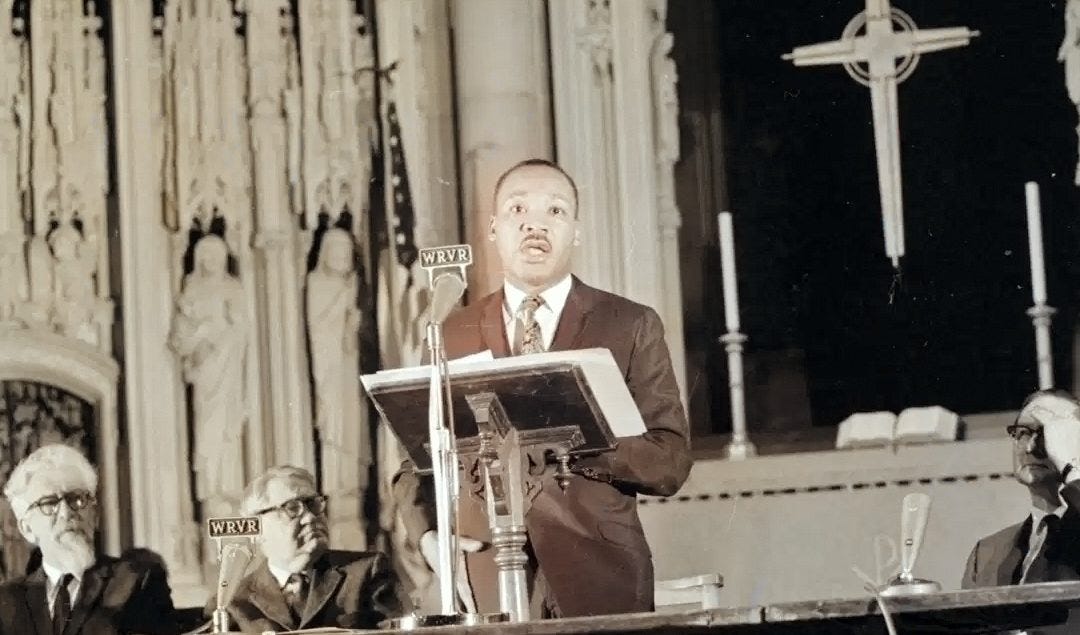

The conversation reminded me of a recurring tension within the Civil Rights Movement—the tension between political strategy and moral clarity. Coates, of course, is the one calling for morals. He says we need to “draw a line” and not cross it, even if that results in foreseeable political drubbings. This is precisely what Martin Luther King, Jr. said (privately) in defense of his choice to speak out against the Vietnam War in April 1967:

I figure I was politically unwise but morally wise. I think I have a role to play which may be unpopular.

Or consider the case of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). At the 1964 Democratic National Convention, the MFDP demanded that its delegates be allowed half of the Democrats’ seats. (They were excluded from the all-white Democratic Party.) The MFDP’s Fannie Lou Hamer turned up the heat with a now-legendary speech. But LBJ didn’t want to alienate Southern Democrats. So he offered a compromise: the MFDP could seat two delegates, which was better than nothing. MLK and Bayard Rustin urged the MFDP to take the deal. But the party had no interest in compromising. As Leslie-Burl McLemore put it, “we had God on our side.”

I knew in my mind, because I’m 23 years old and I’m vice chair of the Freedom Democratic Party, I’m not going to accept that damn compromise.

The result was that the MFDP seated zero delegates, and the state’s white delegates walked out. To my knowledge, none of the MFDP’s leaders have ever expressed any regrets about this. As Unita Blackwell would put it over two decades later: “we came back with our dignity because we did not take the compromise.”

In my view, Klein’s calls for strategic thinking are missing a bit of this history.

IV. Where Coates and I part ways

Coates is right about something big: political strategy isn’t everything. Even in successful movements, there will always be some True Believers who lack any appetite for compromise.5

But Coates is also missing something big.

He starts off great. Like Táíwò, Coates says there are ground rules that people have to follow in order to be worth talking to. Coates is happy to debate affirmative action (etc.), but he draws the line at throwing “epithets at people” and thinking it’s “OK to dehumanize people.” You can probably guess Klein’s reply:

And so what do you do with the fact that so many people think that is OK?

What happens if 35% of the country, 40% of the country, the dominant political force in the country, is inside that? Does that change anything or not? Does the line just hold?

And you can probably guess Coates’ counter:

No. I mean: Welcome to Black America. That’s our history. The line we have drawn in general has not been majoritarian politics, unfortunately.

So far, this is just the usual morality/strategy tension. Coates isn’t confused. Like King (in his idealistic moments) or Blackwell, Coates is simply choosing to be “morally wise” at the expense of medium-term politics. That’s what it means to “draw the line.”

But the problem isn’t drawing lines: it’s policing them.

When the MFDP refused to compromise, they made that choice for themselves. They weren’t trying to shame people like King who would have chosen differently. Contrast that with the way that liberals and progressives treated Bernie Sanders when he did an interview on Joe Rogan’s podcast, won Rogan’s endorsement, and tweeted the proof. A typical reaction:

Or take the Human Rights Campaign:

Given Rogan’s comments, it is disappointing that the Sanders campaign has accepted and promoted the endorsement. The Sanders campaign must reconsider this endorsement and the decision to publicize the views of someone who has consistently attacked and dehumanized marginalized people.

Nor was it just the “far left” and “progressive groups.” Read it and weep, centrists:

This is not the typical, healthy behavior of True Believers. This is something else. It is the performance of True Belief. The insistence on True Belief. When Biden shamed Sanders for “compromising,” he was policing a line in the sand rather than drawing one for himself. He was imposing his own moral decision onto others, demanding that they not cross his line.

(Also notable: Biden wanted to beat Sanders in the primary. That gave Biden an incentive to come up with some line, any line, to shame Sanders for crossing.)

Klein doesn’t have a clear analysis of this sort “counterproductive disengagement,” but it’s clearly the thing that’s bothering him.

I think of the huge backlash to Bernie Sanders for going on Joe Rogan’s show because Rogan was transphobic. Such a big backlash that when I defended him—I became a Twitter trending topic. And to Elizabeth Warren for going on Bill Maher’s show—Bill Maher is Islamophobic. There were protests at Netflix when they brought on Dave Chappelle.

And now we can see the missing piece in Coates’ arguments: he doesn’t justify the backlashes—only personal choices. You don’t have to watch Chappelle if he crosses your line. You don’t have to go on Bill Maher and Joe Rogan. That’s all well and good. But isn’t it a problem for liberals if they won’t let other liberals go on Joe Rogan? What if liberals need the support of Rogan’s listeners to win the next election? Should they really be sniping their own ambassadors?

(Again, don’t forget about incentives. In a society where shaming is an easy way to hurt your rivals and raise your status, expect all kinds of stigma entrepreneurs to pop up, peddling their grimy wares.)

V. Conclusion

Táíwò, echoing Osiel, is right that society needs shame. Coates, echoing King, is right that everyone gets to draw a line. But none of this implies that shame can take the place of good old-fashioned persuasion, or that we should be shaming persuaders for “crossing the line” into hostile territory.

When you think about it, the very idea of “the line”—a single, unique boundary that none shall pass—doesn’t make a lot of sense in the context of partisan politics. Won’t each party want to draw a different line? Won’t the losers typically need to cross their own line—or redraw it—if they want to win next time?

The proper home of “the line” is Osiel’s common morality. But that’s because the line has to be something genuinely common. A corollary of this is that the line had better be neutral on partisan issues wherever possible. We should all want a line that rules out dishonesty, disrespect, hate, and bigotry. But you don’t want to be “inferring these vices from the side which a person takes,” to quote Mill in On Liberty. Otherwise, your side will see the other as forever off-limits for persuasion. The line is supposed to enable tough conversations, not prohibit them.

My guess is that this—the threat of self-imposed exile from the national discourse—is the deep, murky problem that Klein’s been grasping at. It’s a problem that arguably afflicts the right as much as the left. It’s an unglamorous problem, the sort that’s hard to bring up without annoying your teammates. But it’s a problem we need to address. It isn’t going to solve itself.

Enough is enough

I started BIG iff TRUE last April for a very simple reason: I thought the name was funny.

More accurately, “eulogy” is more common by four orders of magnitude.

Táíwò starts by saying that Klein overrates Kirk’s debates and overlooks the death threats triggered by his “watchlists.”

Táíwò also objects to Klein’s remarks on violence, citing

the breathtaking carelessness or outright dishonesty in deflecting objections to the specific accuracy of this portrayal of Kirk with claims about the general appropriateness of political violence.

I’m not sure I feel the force of this. Where’s the deflection? Klein concedes the factual claims in the objections (Kirk made a watchlist, etc.), but he rejects the moral charge of “whitewashing.” He does so for two reasons:

Even given that Kirk was no saint, and even if we opposed his political aims, it’s not enough to condemn his murder: we have to start finding more common ground in this country, or we’ll no longer “feel ourselves as one body politic.” (Which is bad.)

Kirk wasn’t some fringe figure, the rare exception with whom we have no common ground. “Kirk’s worst moments were standard-fare MAGA Republicanism.” MAGA won the White House. You can’t expect to exclude a winning coalition from the body politic!

These arguments aren’t invincible, but they do at least seem reasonably honest.

Later, Táíwò walks back the equation of wokeness with shaming in general:

That is not to say that we can’t try to shame better. We don’t need either the blinkered, toothless standards of 1990s “political correctness” or the exuberant overreach of 2010s social justice culture—neither, ultimately, was equal to the task of squaring the new egalitarian aims of political life with the inegalitarian history that produced our social and political habits. But we do need the core aspect of them that makes Klein so uncomfortable: Russell’s expectation that those who relate to others as though they are not worthy of respect ought to be treated with the regard that orientation deserves.

Let me mention one other notable passage on the topic:

This shame and pressure [i.e. wokeness] did not rely principally on the “the force the state could bring to bear on those it seeks to silence,” as Klein rightly laments.

“Rightly laments”? That makes it sound like Táíwò wanted state-backed wokeness. (My guess is that this is a typo, and the point is supposed to be that the state force itself is lamentable.)

If you ask me, Klein was probably thinking of Federalist 10, where Madison argues that the only way to prevent the rise of political “factions” would be to massively restrict freedom—a cure “worse than the disease.”

For another example, see my piece on political power, where I talk about the role of True Believers in the movement to kill the “death tax.”

One of the points that emerged for me in the last section about drawing and policing lines is that when you start policing them, you inevitably end up creating greater distances between political movements - your policing will be effective on your co-partisans (pulling them onto the same side of the line), and produce backlash in your non-co-partisans (pushing more of them to performatively cross the line).

> stigma entrepreneurs

YC pitch: "Stigmatization is broken. We need to disrupt stigmatization. Our app is Uber but for shaming"