Last Monday, I finally published my publishing advice, which had been floating around the philosophy dark web since 2022.

The next morning, I woke up to find that Justin Weinberg had shared the piece on Daily Nous, one of the two big philosophy blogs. (Thanks, Justin!) I’ve been reading DN since it started in 2014, so this was a treat.

Then I saw the comments.

On hating

Now, I don’t like to throw around the word “hater.” Often “haters” are invaluable sources of incisive feedback whom we are too quick to dismiss, whether out of hubris or insecurity. I’ve been grateful for your comments here at Big iff True, including the critical ones.

But there are some haters out there.

First up, Pete Rogers:

Or, like me, you could decide the entire publishing process is alienating because:

a. Its an insular conversation among experts with no immediate impact beyond the words on the page wherein one publishes ridiculous sounding titles like:

‘Interrogating the Deflationalist Meta-ethical Anti-Realist Account of Non-Propositional Statments.’ …

Plus (b) it’s not worth the slog since (c) peer review is broken. Pete’s comment isn’t really about my post—it’s more of a broadside against the journal system. He’s hating on philosophy as a profession.

Speaking of which, here’s Slextor Formudgeon:

Philosophy as a profession, and publishing as part of that, is really in trouble if in order to get published we need to simplify our ideas and make them more digestible. …

Philosophy is “intensely hard,” as Slextor points out. We shouldn’t have to make each paper so easy to grasp that it devolves into a LOPP (“least objectionable paper possible”).

Admittedly, I did start my piece by saying journals want papers whose “contribution is immediately obvious.” But that doesn’t mean you should pump out boring LOPPs. Who likes boring papers? I’ve reviewed over 100 papers for journals, and about a third of my rejections were on grounds of boringness.1 I’ve also accepted papers that, in my view, invite serious objections, on the grounds that it’s often better to put out exciting but contentious ideas rather than airtight “normal science.”

Kenny Easwaran made a nice observation, which I endorse:

I find it funny that the top two comments on this thread make opposed points – this one complains that we are spending too much effort making things easy and digestible, while the one above complains that we are being too abstruse and technical!

I think the issue is that there are competing goals of making meaningful and precise points on issues where there has already been centuries of thoughts, while remaining understandable, and it’s really difficult to do either well at all while also attempting to do the other!

Agreed! You should make your papers as clear and simple as you can within the constraint of getting the ideas across—but as Kenny says, that’s a big constraint, which can sometimes require painful tradeoffs.

Enter marketeer:

This is an invaluable guide to the field. Now, if only Plato, Aristotle, Avicenna, Aquinas, Bacon, Hobbes, Spinoza, Descartes, Cavendish, Leibniz, Locke, Hume, Voltaire, Rousseau, Smith, Berkeley, Kant, Mill, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Frege, Russell, Moore, Wittgenstein, Anscombe, Carnap, C.I. Lewis, Peirce, James, Dewey, Kuhn, Feyerabend, Sellars, Brandom, Murdoch, Williams, Nagel, and Parfit had just stuck to writing up and reviewer-proofing medium-sized ideas while avoiding distractions, we’d really be cooking with gas in this field.

We found the hater!

There’s a kernel of truth in here, at least. The great philosophers of yore weren’t optimizing for publishability, and they certainly weren’t aiming to put out “medium-sized ideas while avoiding distractions.”

Thomas put it less snarkily (and more effectively) in the Big iff True comments:

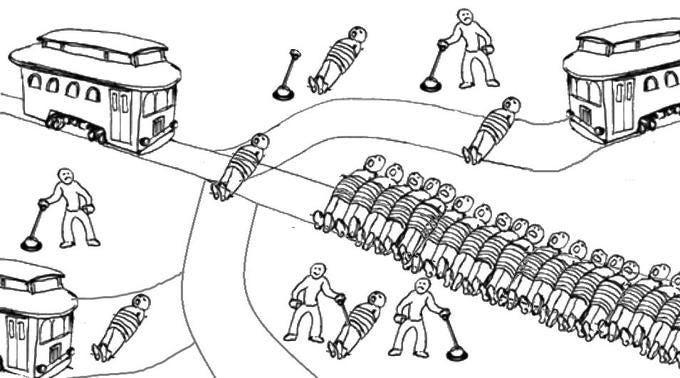

What you say is probably quite right, but I rather hope people don’t follow it. And I doubly hope reviewers don’t take it on board. And that’s because many of my favourite papers would do terribly by these lights, e.g. “Killing, Letting Die and the Trolley Problem.” (How sad it would have been if Judy had received and followed this advice way-back-when.)

I was grateful for Thomas’s comment—and even marketeer’s—becuase evidently I didn’t the purpose of my publishing advice “immediately obvious.”

Write with all you’ve got

Last week, I was giving tips for getting your journal articles published. I didn’t say “write only journal articles,” or “publishing is all that matters.”2

Publishing is part of the job—but of course philosophy is more than a job!

If you want to know what I think people should write, here’s my answer. You should reserve as much time as possible for whatever kind of writing is most meaningful or interesting to you. Try to retain creative freedom and intellectual ambition. Focus on what you really care about, not on trends. Draw on any and all of your favorite writers, whether ancient or modern, philosophers or scientists or poets—write with all you’ve got.

The need to publish

As for my publishing advice, it wasn’t meant for everyone. It was mainly for people who need to publish—PhD students, early career faculty—for whom the process tends to be one of anxiety and frustration.

Not everyone is so stressed—and I don’t just mean peak-era Judy Thomson. Some PhD programs have a culture that makes publishing easier. Students are always sending papers out, sharing stories and tricks, asking for feedback on each other’s drafts. Faculty, meanwhile, are hosting workshops and giving advice.

Many programs aren’t like that, though. Students mostly don’t send papers out. Faculty don’t talk about it. Some students only really learn how it works after they’re out of the nest and on the tenure track, where publishing is their job. As Sidney Hook once wrote, “There are some things best learned not on the job.”3

So that was my target audience: the beleaguered student seeking advice. Not Judy Thomson, Aristotle, or other titanic figures who clearly don’t need my help.

What about the next generation’s Judy Thomson? Aren’t I telling her to write about medium-sized ideas while avoiding distractions?

Yes, I am—if she’s having trouble publishing her ideas! It’s called “publish or perish” for a reason. Anyone who wants a research job has to find some way to get their stuff into the journals. If the next Judy Thomson can’t publish, she’ll never give us the next Realm of Rights, because she’ll get pushed out of the field before she’s had time to develop as a philosopher. We want to keep great young scholars in the field, even if it (perhaps regrettably) means they have to play the journal game a bit.

Of course, if you can publish your best stuff in the fanciest journals without making any compromises in your creative choices or writing style, that’s great. You clearly don’t need my help, either!

Are journals boring and tedious?

This brings me to L.S., our final goodly commenter:

The reality is, however, that in order to get and keep a job in philosophy, one has to publish in a very specific way. Your post provides some pointers for how to excel at that task, but it’s worrying that this is the form philosophy takes now. I am not hopeful that exciting, ambitious ideas can emerge from this process.

I think this is a fair point. (Reminds me of the MacNaughton classic, “Why is So Much Philosophy So Tedious?”)

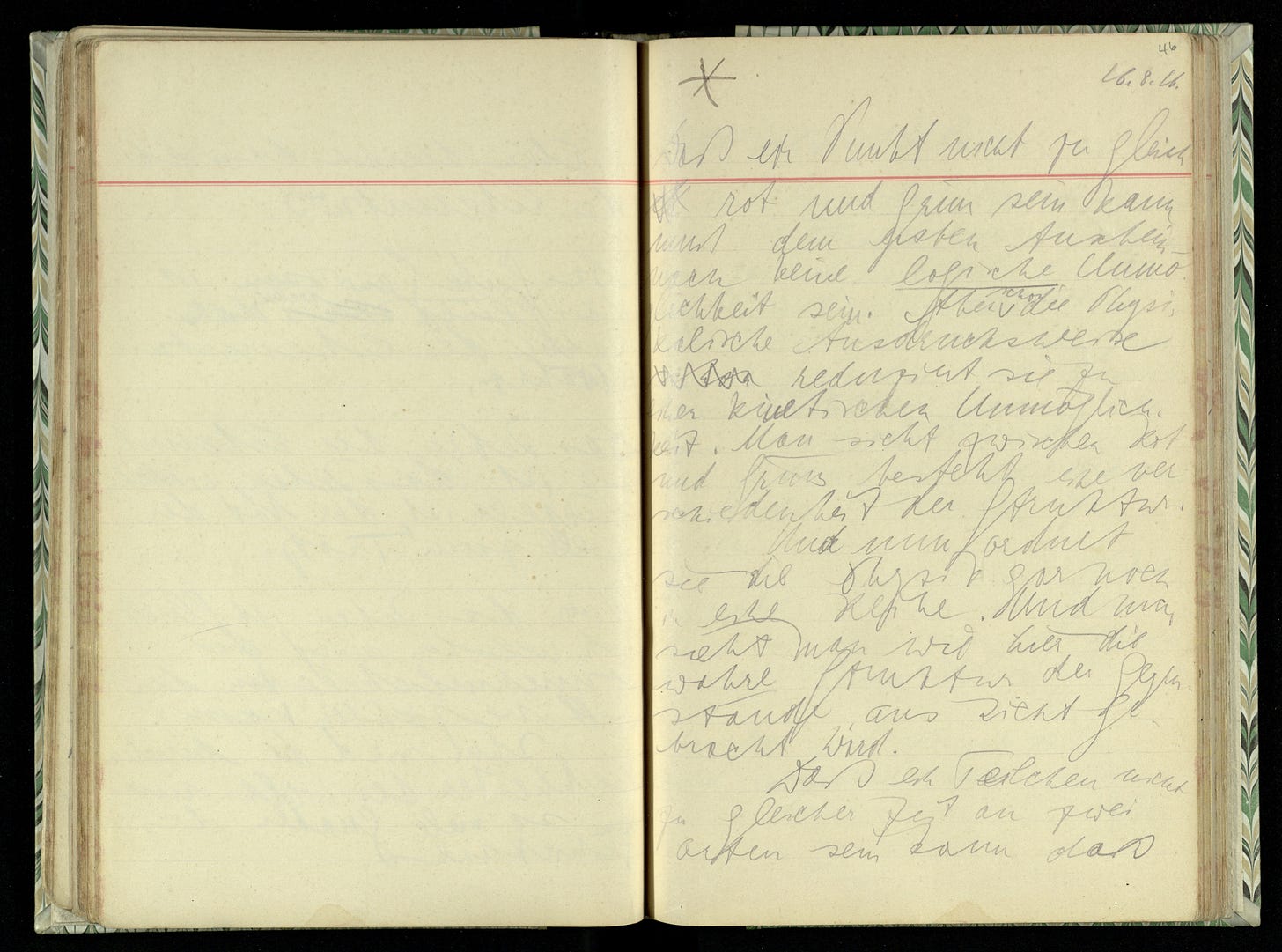

We might take some comfort in the fact that, as long as you spend some time proving yourself in the journals, you can spend the rest of your time writing whatever you want in books, blog posts, wartime diaries (if you’re Wittgenstein), or whatever medium you like.

But I don’t think that’s very comforting. Young scholars spend so much time writing for the journals. It shapes our writing, thinking, and networking. If nothing good comes out in journals, that’s a sign the field as a whole isn’t producing great ideas.

So let me close by replying to L.S.’s worry head-on.

I’ve put together a list of 10 exciting, ambitious journal articles. All of these are from the last year, and they’re all by junior scholars.

Lindsay Brainard, “The Curious Case of Uncurious Creation”

a delightful, careful piece on AI and creativity

Lea Bourguinon, “The Possibility of Act Contractualism”

a totally new look at the fundamental ideas behind a major moral theory

Erik Zhang, “Individualist Theories and Interpersonal Aggregation”

An impressively comprehensive take on the aggregation debate, showing how far we can push one of Scanlon’s main ideas (“the individualist restriction”)

Andrew Lee, “A Puzzle about Sums”

Fascinating piece on infinite quantities, with zero filler

Eli Shupe, “Grave Injustice”

A genuinely shocking paper about the ~30k unclaimed bodies a year that American counties “donate” to medical researchers

P. Quinn White, “Love First”

Admittedly, I’m biased, since I went to grad school with Quinn

But this paper rules – it’s arguing for redoing normative ethics with love as the basic concept, and it has lots of insights along the way (e.g. about plural objects of love)

Hannah Kim, “Imagination and the Permissive View of Fictional Truth”

A careful and convincing treatment of the problem of logically impossible fictions—loaded with great examples

Kyle Blumberg & Ben Holguin, “Fictional Reality”

An elegant argument for an extremely strong view about the determinacy of fictional worlds—and what a title!

Elliot Thornley, “The Shutdown Problem”

A deep and rigorous application of decision theory to the problem of designing AIs so that, in an emergency, they can be shut down

David Thorstad, “Mistakes in the Moral Mathematics of Existential Risk”

Exactly what it says on the tin

Let me also shout out Elise Woodard on partisan deference and Kirun Sankaran and Jake Monaghan on structural injustice. No doubt I’m forgetting lots of people, and no doubt there are tons of great papers that I just didn’t read.

But that’s a good thing! It’s a sign that, in spite of all the perverse pressures, excellent stuff is still coming out in journals.

Our field isn’t perfect, and we should take critics seriously rather than dismissing them as haters. Still, I can’t help but feel that philosophy, as an intellectual enterprise, is in good shape. So many of our colleagues genuinely care about writing clear, interesting papers. That’s a wonderful thing.

The next time you’re feeling hopeless about “that dying profession, academic philosophy,” I encourage you to flip through the latest issues of a few journals. You might be surprised by what you find.

Come to think of it, the last time I got rejected was on grounds of boringness! Specifically, the reviewer thought my paper wasn’t novel because other papers had said similar things.

At first I was indignant. Didn’t I explain what makes my paper special in footnote 8? Shouldn’t the reviewer have reread that note and dwelt on it until they got the message? But that’s just it: the value of my contribution wasn’t immediately obvious.

As a reminder, here’s what I said in the intro:

I am not telling you how to do philosophy, or how much you should publish. I’m just offering advice on how to pick and polish ideas so that, if you want publications, you can maximize your odds while minimizing stress.

From 1946’s Education for Modern Man at p. 217. Hook was a Dewey student, by the way.