The Paradox of Supererogation

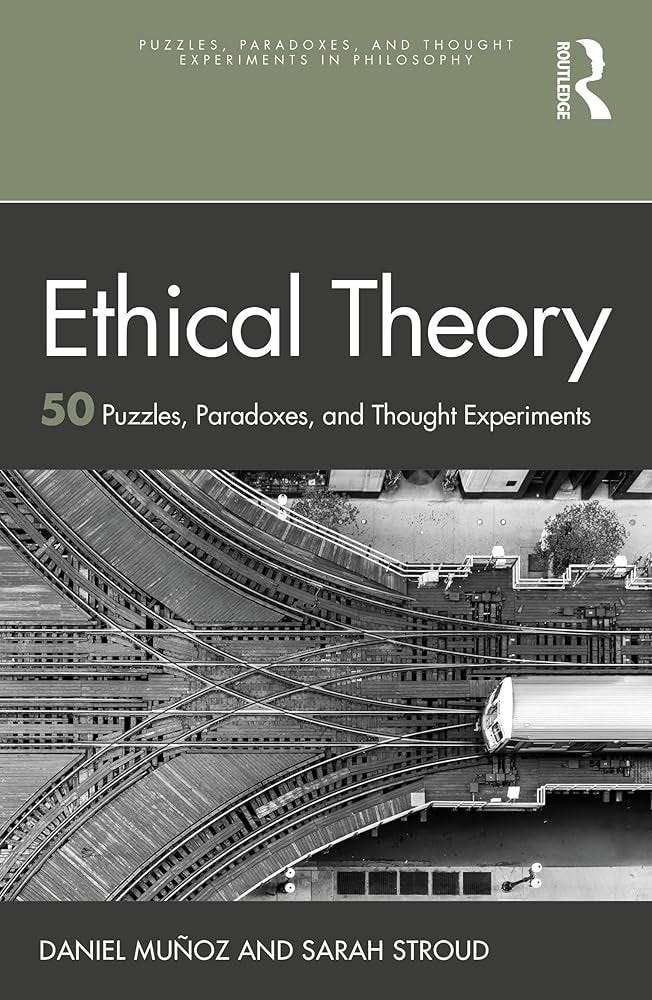

Ethical Theory: 50 Puzzles, Paradoxes, and Thought Experiments (#25), by Daniel Muñoz and Sarah Stroud

Today’s post is another entry from Ethical Theory, my intro book with Sarah Stroud, now available as a paperback or audiobook. (Last week’s entry was Children of Men.)

My thanks again to Sarah and Routledge.

Ethical theorists are always going on about duties—things that would be wrong not to do. But plenty of good deeds seem to lie beyond the call of duty. Philosophers call this sort of thing “supererogation,” meaning “going above and beyond.”

Consider Eli, a (real) philosopher who (really) donated her spare kidney to a stranger. Her decision almost certainly saved that person from years of suffering. If you have chronic kidney failure, and nobody gives you a kidney, your only hope is dialysis: a painful process that requires going to the hospital and having blood drawn from your arm, cleaned in a machine, and sent back into your bloodstream through another tube. A single session takes four hours; a typical week requires three sessions. This goes on for the rest of the patient’s life, unless one can receive a transplant. And since buying a kidney is illegal (virtually everywhere in the world), that means the only hope is to wait for someone like Eli to step up and donate.

Clearly, Eli’s choice was an admirable one. We think she deserves praise and that more people should try to emulate her. But was she just doing her duty? Was she morally obligated to make that sacrifice for the greater good?

Many ethicists would say no. Not because they think Eli did the wrong thing. Donations are a fairly safe procedure. She prevented a big harm at the cost of a small harm to herself, which is a positive thing, not a negative.

Instead, they would call Eli’s action supererogatory. When it comes to her own body, she is the one who should get to choose. So, on this view, she may choose not to donate her kidney, even when donating would be for the greater good. The same goes for smaller local kindnesses, like favors for friends or thoughtful gifts to family members. These actions are, for the “supererogationist,” better than a permissible alternative, but not obligatory to do.

This might strike you as a suspicious combination. In general, it’s your duty to do good things: telling the truth, keeping promises, respecting rights. But donations and favors seem like good things, too. So why aren’t they just duties? Why would morality let you get away with mediocrity?

Philosophers call this the Paradox of Supererogation. There is a deep tension between the two sides of supererogation, its goodness and its optionality. The very fact that supererogatory acts are so very good makes it hard to see why they should nevertheless be optional.

With this particular puzzle, the stakes are enormous. If we can’t solve the Paradox, and supererogation doesn’t exist, we aren’t just going to have to revise our theories. We have to rethink our lives.

Consider how you feel about people who do the wrong thing all the time: scammers who make a living stealing from the elderly, corrupt officials who spend all day exploiting the public, abusers who mistreat their loved ones. What these people do is just monstrous, and anyone who does this sort of thing ought to feel terrible about themselves.

But if supererogation isn’t possible, we are probably monsters, too. How many of us can say that, with every day of our lives, we are doing the very best things we could be doing? Anyone who spends their spare cash on lattes—or their spare time on video games—could probably find something nobler to do. If so, then buying lattes and playing games is not just ethically “meh” but morally wrong. We are quite literally violating our duties when we do anything less than what is best. That is to say, we are doing the wrong thing virtually all of the time.

If that sounds too extreme to you, then you are going to want to find a way out of the Paradox of Supererogation. But what could the solution be?

Responses

The Paradox of Supererogation breaks down into two steps. First: supererogation is supposed to be better than the moral minimum. Second: one has a duty to do the better thing. From this it follows that any would‑be supererogatory act will not truly be optional; one has a duty, not just a permission, to do the best one can.

So, in responding to the Paradox, there are three options.

First, you could give up on the idea that supererogation is better than the minimum. Perhaps we should praise supererogatory acts, but really, they are not better to do. One version of this view says that supererogation is not better than the alternative because it violates one’s duties to oneself. This seems too harsh. Do we really think Eli has a duty to herself not to donate her kidney, and that this duty matters as much as the possibility of saving someone from years of dialysis?

A better option, for the fan of supererogation, is to break the link between “best” and “must.” Donating the kidney is better, on this view, but that doesn’t automatically mean that keeping it is wrong. It is a bit tricky to say why not, however; it can’t just be that we have no duties to help others, since we often do, when we can save someone from a massive harm at a puny cost.

Finally, one could deny the supererogatory, embracing the idea that we are all in a sense moral monsters whenever we do less than best. This seems hard to believe. But maybe it is less extreme than it sounds. Although refusing to do best is wrong, on this view, that doesn’t mean that we should go around enforcing every last duty, the way we enforce the prohibitions on murder and theft. Sometimes enforcing a certain duty can backfire, especially when everybody is violating that duty left and right. Still, even if this view doesn’t call for the enforcement of morality, it does still demand quite a lot of everybody—not just a few good deeds here or there, but the maximally wonderful deed, every single time. Any conscientious person who tries to answer the call of duty would probably end up with “moral exhaustion,” as Michael Schur would call it. Try being maximally wonderful, even just for a day, and see how you feel at the end!

The concept of supererogation, if we can make sense of it, might give us a break from the hassle of being perfectly ethical. But it would still encourage us to strive whenever we can.

Questions for Reflection

Does supererogation seem to you like an incoherent concept? If yes, what’s the incoherence? If no, why do you think supererogation seems coherent to some people?

Is it really so extreme to deny the possibility of supererogatory acts?

Classic Presentation

Joseph Raz, “Permissions and Supererogation,” American Philosophical Quarterly 12 (1975): 161–168.

Responses and Other Treatments

Jonathan Dancy, Moral Reasons (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993): particularly Ch. 8.

Thomas Hurka and Esther Shubert, “Permissions to Do Less Than Best: A Moving Band,” in Mark Timmons, ed., Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics, Volume 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012): 1–27.

Daniel Muñoz, “Three Paradoxes of Supererogation,” Noûs 55 (2021): 699–715.

See Also

Michael Schur, How to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral Question (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2022).

Option 3 has never struck me as that terrible. Yeah, most people don't live up to the standards of perfection most of the time. That's far from "monster" territory. I think people who don't like moral demandingness are a bit too judgy about moral failure. Once you spell out what that actually means in a demanding moral theory, you see that it doesn't deserve the level of castigation we get used to in less demanding theories.

Some thoughts on this:

- The intuition behind insisting on the possibility of superogation seems highly suspect to me--we want some demanding acts to be superogatory because we don't want to feel like we have to do them! (Sidebar: one way of reading the ethics of Jesus is that he insisted that various acts commonly understood to be superogatory were actually obligatory, and that some which the Pharisees, etc. understood to be obligatory were not even that.)

- But! One could say that the failure to fulfill certain (highly demanding) duties is not *blameworthy* (or at least not *that* blameworthy or fitting for indignation and other blame-associated reactive attitudes, including self-directed ones like guilt), because they're so hard for us finite beings, etc., so even if donating your kidney is actually obligatory, you shouldn't get mad at others for failing to do it or feel bad yourself for not doing it.

- I forget if this is the solution you offered in your U of T talk or something I made up just now: You have a right to decide what to do with your body. You have the prerogative to waive that right, but no duty to do so even for the sake of an optimal end. So even though donating your kidney would be optimal, you can't have a duty to do that because you have no duty to waive the right to decide what to do with your kidneys.

- One nice upshot of the above solution: Let's assume you waive certain rights upon entering into certain special relationships. If you become a parent, you waive the right to do whatever you'd like (barring harm to others) with your resources, perhaps even including your bodily resources, because you take on duties to determinate others that demand use of those resources. So if your child gets sick and needs a new kidney, we can say that you have a duty to give your child your kidney (assuming no other kidney is easily available, etc.), even if you wouldn't have said duty to a perfect stranger. (Christian ethics sidebar no. 2: the injunction to "love your neighbour as yourself" could be read as a call to treat our minimal relationships with other members of the moral community as duty-providing in the same way as our special relationships with chosen intimates.) (Chinese philosophy sidebar no. 1: the classical Confucian political ideal casts the ruler as "father to the people"; even Sun Yat-sen is still commonly called 國父 guofu, "father to the nation" or "national father" in the RoC (Taiwan). Confucian ethics is all about duties deriving from special relationships, so maybe the underlying idea here is that the ruler has the parental relationship with the whole people, and therefore takes on the duties of care derived from that relationship *to the whole people*.)

- One problem with the above solution, tho: does that mean minimal costs to your body can never be obligatory? What if Singer's pond is full of brambles that would scratch you as you wade in to save the child--does that mean you don't have to do it, because you have no duty to waive your right to bodily autonomy and endure those scratches? (Chinese philosophy sidebar no. 2: Mencius complains about ethical egoist Yang Zhu, who "would not pluck a hair from his head to save the whole world". So Mencius seems to endorse both demanding special obligations to family and subjects, etc., *and* relaxed obligations of beneficence to strangers.)

- Possible solution to that problem: well, maybe your relevant right is not to choose whatever happens with your body, but to refuse to endure serious costs to yourself. Scratches are no big deal, so you have no right to refuse them and therefore not save the child; but giving up one of your kidneys is a huge deal, so you have a right not to do it. (Where to draw the line though..?)